I’ve been anxiously awaiting the release of Heather Webb’s new book Rodin’s Lover, the story of Camille Claudel, one of Auguste Rodin’s most promising students.

I’ve been anxiously awaiting the release of Heather Webb’s new book Rodin’s Lover, the story of Camille Claudel, one of Auguste Rodin’s most promising students.

I first learned about her art and her tumultuous love affair with Auguste Rodin when a friend recommended that I read Naked Came I by David Weiss (1970).

But then, during my year in Paris, I got to frequent the Musée Rodin, where I could see her work with my own eyes. Haven’t been? You gotta go, although I’m not sure which, if any, of Claudel’s works are on display since the extensive museum renovations. Check the website before you go.

The grounds of the Musée Rodin are like an urban sanctuary in the middle of Paris. There’s even an outdoor café where you can grab lunch.

The old Hotel Biron was a dilapidated mess when in 1908, Rodin first rented out four south-facing, ground-floor rooms to be used as studios. He shared the space with other artists, including Matisse, Isadora Duncan and By 1911, Rodin had taken over the entire building. (Source: Musée Rodin exhibit)

At the time of my visit, Camille Claudel’s work was on display in one of the upstairs rooms of the museum. I would hope and fully expect that her work will return as soon as renovations are complete. The fact that her work is displayed alongside his is itself remarkable. After her love affair with Rodin came to an end (it ended badly – just read Webb’s book) Camille Claudel suffered from financial, professional and mental health issues. Her father supported her, but after his death in 1913, her mother and her brother Paul had her institutionalized, first in Ville-Évrard in Neuilly-sur-Marne, and then, from 1914 until her death in 1943, in the Montdevergues Asylum, at Montfavet near Avignon. Her family rarely visited and refused to bring her home despite the recommendations of the treating physicians.

Before his death in 1917, Rodin continued to provide some financial and artistic support to Claudel, agreeing to reserve exhibition space for Claudel’s works when Hotel Biron was being turned into the Musée Rodin. In 1952, Claudel’s brother Paul finally donated four major works by his sister to the museum. The museum continues to acquire her available works, recently acquiring Young Girl with a Sheaf. Its website features an educational background file on the relationship between Rodin and Claudel, with photos of her best-known sculptures.

Camille Claudel’s sculpture reveals astonishing talent and emotion. Rodin’s influence is unmistakeable in her early work, less so in her later, smaller work.

Camille Claudel, The Age of Maturity (1899), Bronze. Donated by Paul Claudel in 1952. This is a partial view of the sculpture, featuring a pleading woman, often said to be Camille begging for Rodin, who is being torn away by his long-time companion Rose. Claudel herself would reject such an autobiographical interpretation, and instead claim that it is intended to symbolize the grass of youth versus age.

Camille Claudel, The Gossips (1895), plaster. Musée Rodin. Donated by Rodin in 1916. Note Claude’s signature in the lower left corner.

And if this small sampling of Claudel’s work isn’t enough for you, there’s more on the way. In March, 2017, a new Musée Camille Claudel will be opening in Nogent-Sur-Seine, the a small town southeast of Paris where the Claudel family lived when Camille was young. Over 77 pieces of Claudel’s art will be on display, thanks to a large 2008 acquisition by Reine-Marie Paris, the granddaughter of Paul Claudel. Here is a link to a video from French television about the plans for the museum. Finally, here is a link to the website of Reine-Marie Paris which includes photographs of even more of Camille Claudel’s sculptures.

I can’t wait to hear more about the completion of the new museum. It will definitely be worth a drive out to the countryside southeast of Paris.

In the meantime, we will have to content ourselves with Heather Webb’s new book, which breathes life into the passionate, turbulent life of Camille Claudel. Book clubs will find much to discuss, above and beyond the historical interest in a female artist of the late 19th century.

For instance, what do you think drove Camille Claudel to mental illness, if that’s what it was? Was she paranoid about Rodin, or did he really manipulate and compete with her? Which injured her more, the lack of support from her mother and her brother Paul, or a sexist society that made success in the arts so extraordinarily difficult for women? Would Camille Claudel have been better off if she’d never entangled herself with Rodin? Finally, do you see any parallels between Camille Claudel’s struggles and those of 20th and 21st century women?

I’m definitely recommending it to my own book club. Bring some wine!

Rodin’s Lover by Heather Webb: Highly Recommended.

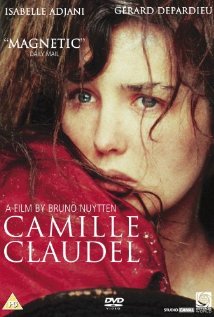

For further enjoyment: Don’t miss the 1988 Oscar-nominated film, Camille Claudel, starring Isabelle Adjani and Gérard Depardieu, available on Amazon Prime Instant Video.

You must be logged in to post a comment.