Demeter’s Choice: A Portrait of My Grandmother as a Young Artist is the story of a young American sculptor named Mary Lawrence Tonetti who began studying under Augustus Saint-Gaudens at a very young age. She came of age in the art studios of New York and Paris in the late 19th century, and is most famous for her sculpture of Christopher Columbus for the Chicago World’s Fair of 1893.

The author is the sculptor’s own granddaughter, Mary Tonetti Dorra, who had access to wonderful personal information to make the story rich with detail and insight. There are even copies of some of Mary Lawrence’s original pen and ink sketches and travel notes.

Demeter’s Choice tells the story of one woman’s choice between art and love. Mary Lawrence led a remarkable, artistic life both before and after her big choice. It’s a life worth knowing more about. And for the followers of this blog who like to hear about art history in Paris, I’ll point out all of the Paris sites and scenes of interest.

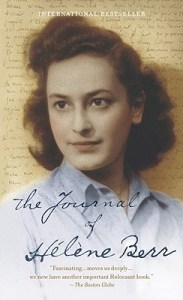

Mary Lawrence Tonetti (1868-1945). Source: sgnhs.org.

Mary Lawrence was a privileged young woman (her ancestors included a mayor of New York and Captain James Lawrence, a famous patriot famous for his wartime utterance: “Don’t give up the ship!”) who began a pampered life in Cliffside, her family’s large estate overlooking the Hudson River in Sneden’s Landing, New York. Mary was known to have grown up with a “robust temperament” and a taste for the outdoors. (Which to me is the Gilded Age way of saying she was a handful, a tomboy, a bit of a rebel. Funny how many of those kinds of Gilded Age girls turned out to be artists, especially sculptors….)

Mary enjoyed art from a very young age. When she was only seven years old, her family arranged for the up-and-coming Augustus Saint-Gaudens to come up to Sneden’s Landing to teach drawing and sculpture to Mary a group of other children. (Not a bad start for a kid!) When she was older, Mary continued art lessons at Saint-Gauden’s Fourteenth Street Studio in the German Savings Bank in New York City. Saint-Gaudens would have a huge influence on Mary’s life and career in art.

Augustus Saint-Gaudens, mentor and friend of Mary Lawrence

The German Savings Bank around 1872, the site of Augustus Saint-Gaudens 14th Street studio. Source: Office for Metropolitan History NYC.

By the time Mary was twenty years old, she was personal friends with Saint-Gaudens’ whole crowd, including the architects Charles McKim and Stanford White. Demeter’s Choice has a lovely scene where Saint-Gaudens, McKim and White joined Mary for a picnic at Sneden’s Landing before she set sail on her first Grand Tour of Europe in 1886. There were hints that Charles McKim, a married man of nearly forty, was already falling in love with her despite their vast difference in age.

Accompanied by a supportive aunt and her more conventional sister Edith, Mary Lawrence made the Grand Tour of Europe, including a summer of sightseeing through Belguim and Germany before she would settle in Paris and begin her art studies it the women’s atelier of the Académie Julian.

Passage des Panoramas, just off of boulevard Montmartre in the 2nd arrondissement of Paris, the location of one of Académie Julian’s atelier for women. The studio is no longer there, but a stroll through the arcade will still give you a sense of the time and place.

Being a friend and an assistant to Augustus Saint-Gaudens opened many doors upon Mary’s arrival in Paris. He introduced her to many of the American artists who worked or studied there, including Mary Louise Fairchild from St. Louis, who was studying with Carolus-Duran and the Académie Julian on a prestigious fellowship. In Demeter’s Choice, the two Marys meet at the opening night of the Paris Salon of 1886, where Mary Fairchild’s portrait of Sara Hallowell was on display. Sara Hallowell was an American art agent for wealthy American art collectors such as Bertha Palmer of Chicago. Sara lived part of the year in Paris developing close relationships with Mary Cassatt, Claude Monet, Edgar Degas and Auguste Rodin. Mary Lawrence was making all the right connections too, a rare opportunity for such a young artist.

Mlle S. H. (Sara Tyson Hollowell) oil on canvas by Mary Fairchild (1886). Property of The Warden and Fellows of Robinson College, University of Cambridge. This is the portrait that was exhibited in the 1886 Paris Salon where Mary Lawrence met Mary Fairchild and Sara Hallowell. Source: http://www.pubhist.com

Within a week of her arrival in Paris, Mary Lawrence was invited to Auguste Rodin’s art studio which he shared with his student and young mistress Camille Claudel. Together they strolled through the studio where Mary got to see the models for The Burghers of Calais and some of the figures from The Gates of Hell. Today you can see these works for yourself at the Musée Rodin, one of my favorite museums in Paris. Inside you can even see some of Camille Claudel’s sculptures as well.

Mary and her sister settled into their apartment at 56 rue Notre Dame des Champs in the heart of the Left Bank of Paris, within a few blocks of some of the biggest names in the art world, such as John Singer Sargent, Carolus-Duran, James Whistler and William-Adolphe Bouguereau. Saint-Gaudens and his wife lived nearby, at 3 rue Herschel just on the other side of the Luxembourg Gardens. Like many Americans ever since then, Mary came to adore Paris, from the macaroons at LaDurée, to the baguettes from her local boulangerie to a lovely stroll through the Palais Royal.

.

Being a young woman of privilege in the Gilded Age meant you had the opportunity to travel throughout Europe instead of having to freeze or starve your way through a miserable winter in Paris. Mary Lawrence left Paris for a few winter months in Italy with her family entourage before she returned to New York in the summer of 1887. By the spring of 1888, she had returned to Paris for another season of classes at the Académie Julian.

Once her second session of Paris art studies were over, Mary returned to New York, where she taught at the Art Students League, served as Saint-Gaudens’ assistant and worked on her own sculpting projects.

In the fall of 1891, Mary learned that she would be awarded a contract to create a statue of Christopher Columbus for the Chicago World’s Fair under the supervision of Saint-Gaudens. It was a huge honor. Most women who received commissions for the fair (such as Mary Cassatt, Mary Fairchild MacMonnies and Sophia Hayden) were contracted through a separate Board of Lady Managers led by the Chicago society queen Bertha Palmer. Mary Lawrence received her commission directly from the Fair Commissioners, who were all male. You can read a fun 1893 New York Times article about Mary’s commission here.

Demeter’s Choice tells the wonderful story of a fight between Mary Lawrence and her supporters versus Frank Millet, a particularly odious fair organizer, who objected to the prominent placement of her Columbus statue because it was made by a “female novice.” Millet actually arranged to have it moved to a spot near the train station. You’ll have to read for yourself to learn what happened next. If you look at the image below, it is amazing what a good job young Mary Lawrence did – she was young, but certainly no novice.

After the excitement of the Chicago World’s Fair was over, Mary went back to Paris. She continued her studies at the Académie Julian and renewed her many friendships with the artists of the Left Bank and beyond. Mary was on everyone’s guest list, attending soirées hosted by the likes of Charles Dana Gibson and James Whistler. It was at Gibson’s glamorous ball and then again at Whistler’s home at 110 rue de Bac that Mary Lawrence met François Tonetti, a sculpting assistant to Frederick MacMonnies. The rest, as they say, was history.

Even after she met the charming and passionate François, Mary Lawrence continued to work as a sculptor in her own Twenty-Third Street studio in New York and to teach Saint-Gaudens’ classes at the Art Students League through most of the1890s. Charles McKim continued to pursue her, as did François, her favorite Frenchman.

Saint-Gaudens didn’t want his protégée to marry, worried that she would give up her art for a house full of “festive children.” He asked: “wIll she just die and fade into the wife of François Tonetti…?” Others objected because François wasn’t from the “same stock” as the Lawrences. Mary’s own sister pressed her to choose Charles McKim, who offered a more proper and promising future than a bohemian artist could.

No matter what choice Mary Lawrence would make, it was clear that she wouldn’t die and fade away. She would always live in a world of art. Mary Lawrence lived the rest of her life surrounded by artists, founding and developing an artist’s colony in Sneden’s Landing. Generations of artists and actors have enjoyed living there, including Gerald and Sara Murphy, Orson Wells, Lawrence Olivier, Vivien Leigh, Al Pacino, Angelina Jolie, Bill Murray and Mikhail Baryshnikov. Just for fun, you can check out this recent gossip article about Tom Cruise checking out the real estate in Sneden’s Landing.

Quite a story and quite a legacy. We are so lucky that Mary Lawrence’s granddaughter wrote it all down.

Author Mary Tonetti Dorra has a list of appearances scheduled in early 2014. You can check them out for yourself on her website.

Review and Recommendation by Margie White of the American Girls Art Club in Paris

You must be logged in to post a comment.