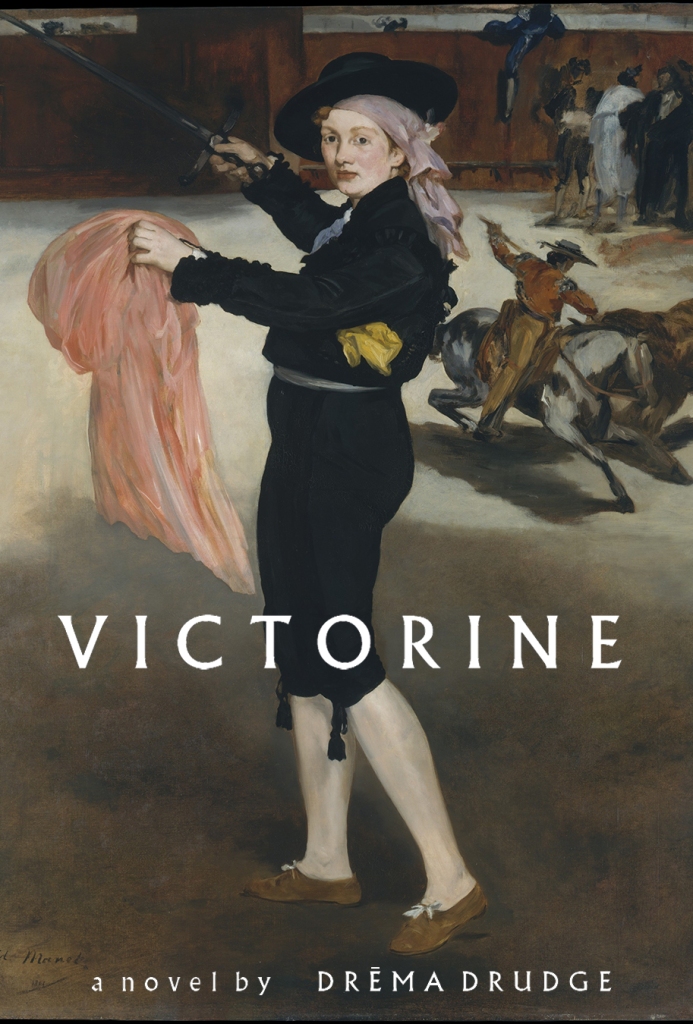

Author Drema Drudge has a new novel about Victorine Meurent, one of Edouard Manet’s favorite models, the infamous star of Olympia at the Musée d’Orsay. You could say that this novel is Meurent’s coming out party. She steps out of each painting and comes alive with her own irrepressible voice.

I’m happy to say that I might have walked in the footsteps of Meurent in Paris. I once visited Manet’s studio near the Gare St. Lazare, at 4 rue St. Petersbourg. Manet painted here in the 1870s, including the period when Meurent posed for his painting The Railway (1873). Did Meurent walk through these very doors as she met with Manet?

One of the many things I enjoyed about the novel Victorine was the way Drudge titled many of her chapters after a painting. So for example, Chapter One is Portrait of Victorine Meurent, Paris 1862, and features Victorine posing for Manet for the first time at his studio on rue St. Petersbourg. Another chapter is named after the painting on the cover (above), Mademoiselle V . . . in the Costume of an Espada.

I don’t know about you, but I just can’t read a book about art without Googling the paintings. Or better yet, go see them in person. So hang on for a little treat: here are some of the paintings that come up in the book, including – in great triumph over the many obstacles in her way – Meurent’s very own. I’ll tell you where you can find them so you can put it on your art museum bucket list.

One thing kept coming back to me as I read this book. Meurent’s story is quite different from most of her contemporaries, whose family wealth supported them through their art schooling and beyond. Women whose stories are more familiar, like Berthe Morisot, Eva Gonzales and Mary Cassatt. Meurent would have been jealous of the opportunities these women had, including the opportunity to befriend and begin painting with Manet. Manet and Meurent might have been friendly, but she was never his equal. She wasn’t of the same social class.

Nevertheless, you will see that after decades of modeling for others, Meurent finally enrolls in Académie Julian‘s evening classes for women (which for some reason cost twice as much as the same classes for men). It was there she learned the essentials of oil painting – things she could never learn from merely eavesdropping and observing as a model. We hear Meurent’s frustration with the way the privileged women in her classes take their opportunity for granted, wasting paint and supplies.

In fact, as I think about it, nearly all the American women artists who studied In Paris during the late 19th century enjoyed some level of wealth and comfort, for example: Ceclia Beaux, Elizabeth Gardner Bouguereau , sisters Lydia, Rosina and Jane Emmett de Glehn, along with their cousin Ellen (“Bay”) Emmet Rand, Ellen Day Hale, Lilla Cabot Perry, Dora Wheeler, Mary Lawrence Tonetti, Anna Klumpke, Enid Yandell, Fanny van de Grift Osbourne – the list goes on. Some of these women may not have been wealthy but were fortunate in other ways: Abigail May Alcott Nieriker‘s sister Louisa May Alcott subsidized her travel and art studies from the sales of Little Women and Mary Fairchild MacMonnies obtained a three year scholarship from the St. Louis School of Fine Arts, where she had been the first female art instructor.

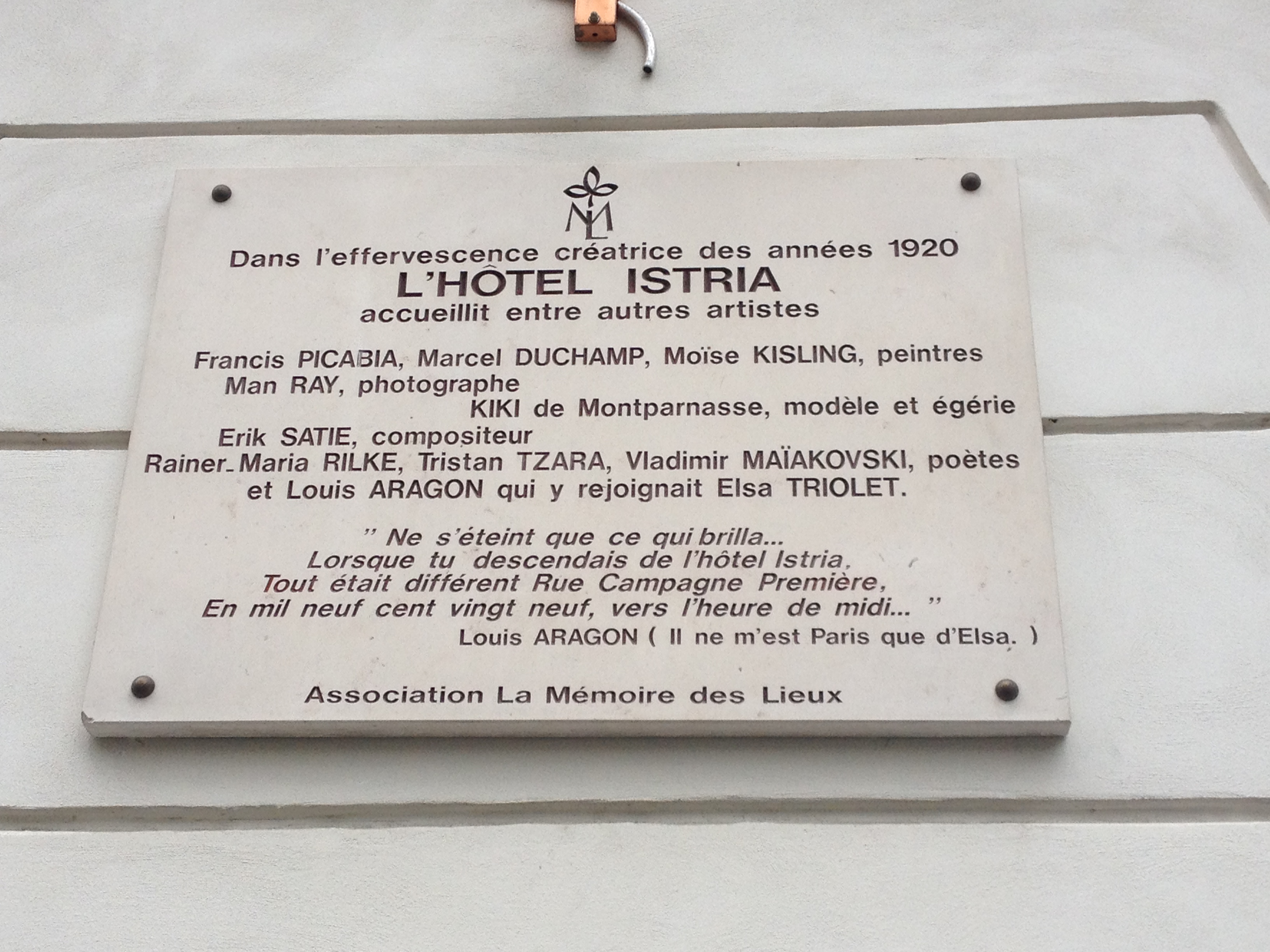

The stories of all of these women art students make fascinating reading, but their tales differ greatly from Meurent’s. They faced discrimination based on their sex, but in Meurent’s case you must factor in poverty and the social shaming that came with it. Parisians treated Meurent like a prostitute because she had dared to pose like one; Parisians spat and jeered at her in public after Manet exhibited Olympia at the Paris Salon. However, Meurent was fearless, something upper class women could not dare without damaging their reputation. Meurent went out to the cafés, bars and studios of Paris without a chaperone, and in that sense benefitted somewhat from the social network that male artists enjoyed. Don’t get me wrong – they didn’t treat her like an equal, more often than not, they were trying to make her their next mistress – but at least she wasn’t in a gilded prison like Berthe Morisot or Mary Cassatt.

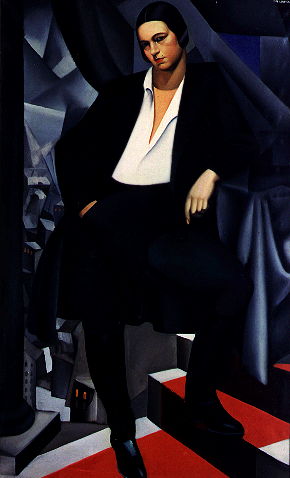

Within one year after Meurent began her studies at the Académie Julian, she got a self-portrait accepted into the Paris Salon. She continued to exhibit there in various years from 1876-1904. You can see more of Meurent’s paintings on Drema Drudge’s website, but I’m not sure where to find them, except for this one, which can be seen in a small art museum in Colombes, France, on the outside of Paris near Argenteuil. Apparently, Meurent lived in the village of Colombes until her death in 1927. She outlived Manet by 44 years.

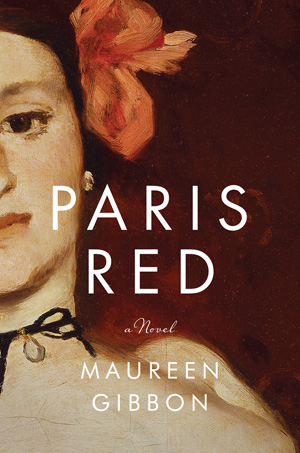

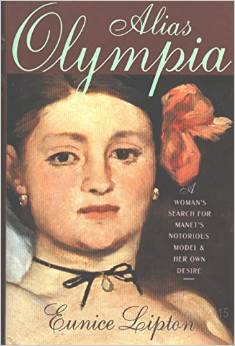

For additional reading:

Alias Olympia: A Woman’s Search for Manet’s Notorious Model and Her Own Desire by Eunice Lipton

The Parisian Sphinx, upcoming nonfiction by Summer Brennan (cover not final)

You must be logged in to post a comment.