I Always Loved You is Robin Oliveira’s wonderfully atmospheric story about Mary Cassatt’s early years in Paris, beginning in 1877 when Edgar Degas invited her to exhibit with the revolutionary group of French artists known as the Impressionists. Oliveira has done a fabulous job of capturing the place and times of these 19th century artists, including Degas, Morisot, Manet, Renoir Caillebotte and Pissaro.

Oliveira offers us lively and colorful scenes in Paris, from the studios of Montmartre to the salon scene along the Champs d’Elysée. I have photos of some of these scenes in an earlier post called Mary Cassatt’s Greater Journey, including her homes on avenues Trudaine and Marignan.

As the title suggests, this book imagines that there was more to the story of the friendship between Mary Cassatt (1844-1926) and Edgar Degas (1834-1917). Degas and Cassatt were known to be very close friends and colleagues. It is absolutely true that Degas had an enormous influence on Cassatt’s art and life. But was there ever more? Oliveira imagines their story as a love story.

But wait. Wasn’t Degas the disagreeable painter of nude prostitutes, working class absinthe drinkers and the petit rats from the demi-monde of the Opéra? He had a bad reputation, if rumors are to be believed. Some have made him out to be celibate, impotent, a misogynist, or even a sex offender.

And wasn’t Cassatt a cloistered woman of high social standing, best known for her tender portraits of mothers and children?

What could these two possibly have in common? Despite their differences, there was something that bound the two together, and I believe it was their fanatic devotion to their art. They both worked brutally hard at their technique and admired that in each other. They loved capturing the color of flesh and preferred to paint indoors, unlike many of the other Impressionists. They were the most experimental of the Impressionists, spending a great deal of time working and re-working their prints.

Was there ever more than this professional bond? We will never know. Cassatt destroyed all of her letters with Degas before she died. Oliveira draws her own inferences from that big mysterious gap, but I’m not so sure. Can’t Cassatt’s extraordinary work speak for itself? Isn’t her true story – as far as we know it – enough? Isn’t it enough that Cassatt and Degas had an intense, complicated, or even tortured friendship? Why do we have to impose on her our desire for romance?

This story is different than the one about the love affair between Edith Wharton and Morton Fullerton that Jennie Fields wrote about in Age of Desire (2012). That imagined story was based on Edith Wharton own letters. Her late-in-life extramarital affair might have been a surprise to Wharton’s many fans and admirers, but it was undeniably true. And with it came the revelation that Edith Wharton had written her own erotica. Quelle surprise!

The Cassatt-Degas question is similar to the one between Berthe Morisot and her brother-in-law Édouard Manet, whose story is also told in Oliveira’s book. There were rumors of a romance there too, and inferences to be drawn. Both Morisot and Manet left behind some remarkable paintings that give us a potential peek at their inner secrets. I’ve written about this in the past – you might want to check out this previous post, Berthe Morisot’s Interior.

So are there any clues in Degas and Cassatt’s work?

Degas made numerous drawings, prints, pastels and etchings of Cassatt in the years between 1879 and 1885. But there is not one nude, no sweet smiles or sultry stares. Mary Cassatt would never have subjected herself to that kind of exposure. All we have are inscrutable poses like this:

Mary Stevenson Cassatt by Edgar Degas, Oil on canvas, (1880-1884), National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution.

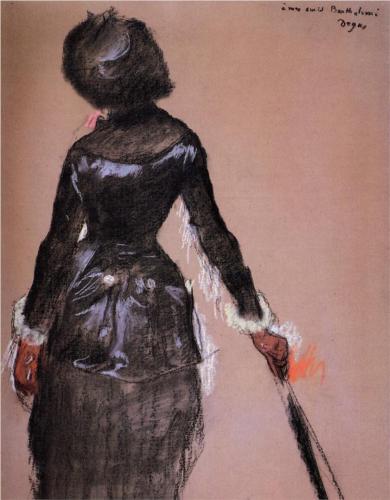

Degas made a series of studies, drawings and prints of Mary and her sister Lydia at the Louvre, including this study of Mary’s silhouette:

The second pose is flattering, and has an unmistakeable sense of Degas’ interested gaze, but it is a long way from suggesting that they were lovers.

And yet it nags us, if there was nothing improper, why would Cassatt destroy their letters? It is entirely within this mysterious gap that Oliveria’s book takes place.

The letter burning story does make for lovely opening and closing scenes in I Always Loved You. Cassatt is elderly and living with no one but her long-term housekeeper at her country home, the Chateau de Beaufresne, and she is reading the letters she and Degas wrote to each other.

But she had kept these letters, as he had kept hers, though what they had been thinking, she couldn’t imagine. Such recklessness. Private conversations should always remain private. Why should anyone know what they themselves had barely known?

At the very end of the book, Oliveria returns to this same scene and shows Cassatt sitting in the dim light next to the fire, nearly blind from cataracts, as she decides to destroy the letters.

Was it a crime to burn memory? She didn’t know. Memory is all we have, Degas had once said. Memory is what life is, in the end.

She would be ash herself, soon, like all the others. She thrust the letters one by one into the fire. . . .

The pages burned on and on. And in those flames the years evaporated, the things unsaid and foregone, the misunderstandings and misconceptions and subverted hopes, the things that would now never be said.

Did they or didn’t they? We’ll never know for sure. Oliveira’s book offers one possible interpretation. What’s yours?

Mary Cassatt at Chateau de Beaufresne, undated photo. Source: http://www.mary-cassatt.net

Chateau de Beaufresne (2012 photo). Source: http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Château_de_Beaufresne.JPG

If you’re a fan of Mary Cassatt and would like to see more photos of Chateau de Beaufresne and the family gravesite nearby in Mesnil-Théribus, go to http://www.mary-cassatt.net. I hope to get there myself on my next trip to Paris.

You must be logged in to post a comment.