In The Footsteps of Cecelia Beaux

I once spent a whole day in Paris walking in the footsteps of Cecelia Beaux. I’d read her autobiography and was eager to feel the same Paris that she did. I mapped it all out and took my camera. When I tried to tell friends and family back home about my little adventure, it nearly broke my heart when they said “Who?”

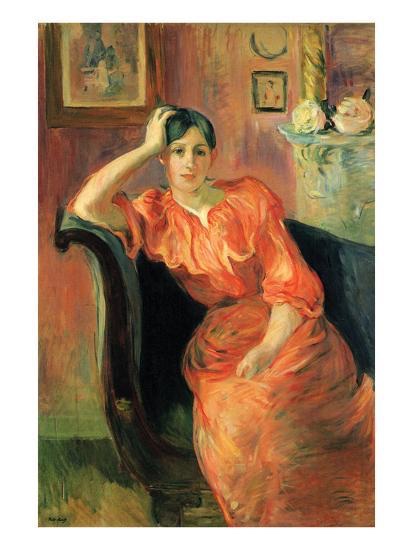

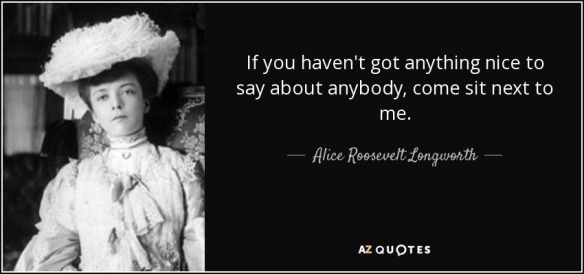

Celia Beaux, Self Portrait (1894)

That’s when I pulled out the famous quote from William Merritt Chase, and said pretty indignantly, well, another famous artist once said “Miss Beaux is not only the greatest woman painter, but the best that has ever lived.” — William Merritt Chase, 1899. And they raised their eyebrows, like, “really?”

So that’s when I resolved to dig deeper into Cecelia Beaux’s story. Who was she and why has her legacy faded so much in the last 100 years? And what about that interesting praise from William Merritt Chase?

Wholly aside from the gender politics within that quote, Chase is making an unavoidable comparison between Cecelia Beaux (1855-1942) and Mary Cassatt (1844-1926). Cassatt would have been the main competition for the honor, such as it is. And yet today, Mary Cassatt is a household name and Cecelia Beaux is not.

It shouldn’t be that way.

Beaux and Cassatt’s Beginnings

Cassatt and Beaux had much in common. They each had French blood: Beaux’s father was from Avignon, Cassatt’s ancestors on her father’s side were French Huguenots from Normandy. Both Cassatt and Beaux spoke fluent French, which might just seem like an interesting coincidence, but then, they both found success in Paris art circles, which is no small thing for an American. Beaux later attributed her talent to “the priceless heritage” she received from her French father, who did indeed have some natural talent for art, often drawing charming little animal sketches for his daughters.

Both Beaux and Cassatt were raised in Pennsylvania in the mid-1800s. Their well-off families could afford to support their art studies, although the Levitt-Beaux family was less so due to some reversals and hardships, including business failures and the death of Cecelia’s mother 12 days after her birth. However, both families still considered themselves “proper” and tended to follow the social proprieties of the Victorian era, which limited the opportunities for their daughters.

Cassatt (1844-1926) was a decade older than Beaux (1855-1942), but they both started studying art at a very young age, first privately and then at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts (PAFA) in Philadelphia, Cassatt from 1860-1862, Beaux from 1876-1878.

Together, their stories reflect the achingly slow pace of change in 19th century art studies for women. Cassatt studied in PAFA’s Antique Class (copying from plaster casts) from 1860-62 during the “fig leaf era,” a time when women were deemed too sensitive to observe sculpture in mixed company unless the male sculptures were discreetly adorned with fig leaves. There were no life drawing classes for women. In 1860, Cassatt’s class of women did receive permission to pose for each other, but it would only be for one hour at a time in a private modeling room and without an instructor. And one would assume with their clothes on. Given these restrictions, Cassatt left the United States to travel and study art in Europe with her family in 1865, when she was only 21 years old.

In case you missed it, I’ve previously written about Mary Cassat in Paris and in her country homes outside of Paris, Chateau de Beaufresne in Le Mesnil-Theribus and Bachivillers, France.

Beaux’s Art Studies in Philadelphia

Unlike Cassatt, Beaux studied art in Philadelphia for over 10 years, beginning at age 16. Her studies would be very start-and-stop as she hopped from one teacher to another, and given the limitations of her early instruction, her talents would be slow to develop. Which just goes to show that Linda Nochlin (author of “Why Are There No Great Women Artists?”) was right, it really does matter how you study art and with whom.

From the beginning, Beaux’s studies were subject to the approval of her uncle, William Foster Biddle, not her father. Beaux’s father had returned to France in 1861 after his American textile business failed, and did not return for 12 years. He left his daughters in the hands of their grandmother, their aunts and their Uncle Will, who would act as the patriarch of the family.

By the time Beaux was 16 years old, it was clear she did not excel in her academic studies at the Lyman School for Girls. “My reports were not bad, but they were not very good,” admitted Beaux. In 1871 Uncle Will decided she could quit school and pursue art studies instead. He sought not professional instruction but a ladylike approach suitable for a young woman who would soon be thinking of marriage.

Professional art classes at the PAFA were out of the question. The progressive women students of PAFA had filed a petition to enroll in life drawing classes. While the petition was granted in 1868, they were only allowed to use female models. Still, Uncle Will would not have approved. He was spared that decision because in 1870, PAFA closed its doors in order to build a new building with much more room for art classes. His niece would need to study elsewhere.

Standing since 1876, The Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, 118-128 N Broad St, Philadelphia, PA

Uncle Will was able to make what he thought to be a thoroughly safe choice for Beaux’s first teacher: his own relative Catherine Ann Drinker (“Aunt Kate”), who had already studied at PAFA and opened her own studio by the age of 30. As Beaux herself said, “I think that, secretly, my uncle shrank from launching me away from the close circle of home, and thought that if I must go out, I could not be in a safer place.” Beaux’s studies with Drinker, which started in 1871 and lasted only a year, consisted of making conté crayon copies of lithograph copies of Greek sculptures. (So in other words, Beaux would be 3 times removed from actual contact with a real live model. Can’t get much more proper — or inadequate — than that.)

It turned out that Beaux was frustrated with her drawings at Catherine Drinker’s studio, calling them “correct and ugly, a hateful travesty to the eyes.” But Drinker offered a different kind of education: what the life of a professional female artist could be like. It turns out it was more sophisticated and social than Uncle Will had expected. Drinker invited Beaux to stay at the studio after lessons were over and to join her artistic circle of friends. Beaux was inspired but Uncle Will was not pleased.

When Drinker became engaged to one of the men in her circle (a man 8 years younger, go Aunt Kate!), she recommended that Beaux sign up for art school. Knowing Uncle Will would expect a segregated class for women, Drinker recommended a class offered by the Dutch artist Francis Adolf Van der Wielen.

Beaux entered Van der Wielen’s class in 1872, but was required to prove herself proficient in enlargements and perspective in order to be promoted to the Antique Class, where she would draw copies of plaster casts.

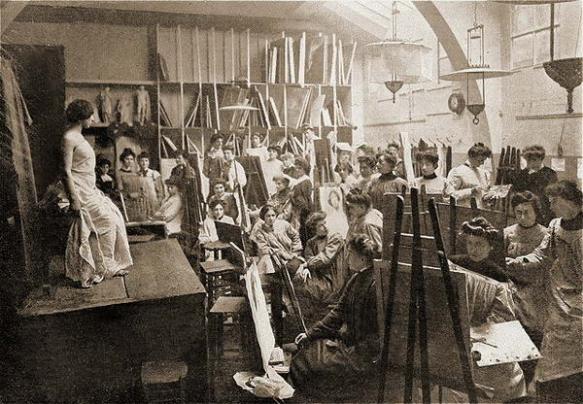

Undated photo of a drawing studio at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, in what would have been an “Antique Class.”

In her autobiography, Beaux offers a delightful rant that explains exactly why copying from plaster casts was such an “impoverished” way to study art.

I soon found myself before a large piece of white paper and one of the plaster busts. It was not the head of the Medici Venus, which I had never seen, of course, but something like it, and even less interesting, and it was placed in a broad hard light and had no silhouette, or mystery of lighting, no motivity. It was an object which took me nowhere and brought me nothing, as I now see, because it represented a series of contradictions. I suspect that it was a Roman bust, and without original impulse. Of course, it had the highly sophisticated syntheticism of the Greek ideal for its origin, but refined away to negative import and diluted artificialdom, it had only in the plaster pretended substance, which the marble would have made existent and absolute, even in abstraction.

The surface of plaster of Paris gives no clue to its substance, though the forms it is the mould of were decisive, though abstract. So firm, in fact, that thinking back to the original that must have been, the idea of youthful body, tender cheek, lip and throat, seem to have been qualities to be rejected.

Beaux wrote these impassioned words nearly 60 years later, after she had spent most of her life painting with live models. I don’t believe I’ve ever heard a better explanation why women needed to be allowed to draw and paint from life, and not the cheap plaster casts available in their “Antique Classes.”

Beaux’s fondest memory of her year with Van der Wielen was when a fellow student brought in a gift from her fiancé, a young doctor, complete set of bones of the skull. The students copied them all in pencil, enjoying the play of organic curves, modeling and lighting for the first time. Years later, Beaux credits this knowledge of the human skull for giving her a “predilection for portraiture, and the manifestations of human individuality. I always saw the structure under the surface, and its capacities and proportions.”

Classes at Van der Wielen’s would end in 1872, when a female student “succumbed to the manly charms of our director,” and with “her ample fortune floated them away, far from the ennui of class exercises in drawing.” (Isn’t Beaux hilarious?)

Van der Wielen’s departure would lead to a teaching opportunity for Beaux. Catherine Drinker stepped into Van der Wielen’s position and in 1872, Beaux stepped into Drinker’s post as a part-time art teacher at Miss Sanford’s School for Girls. Beaux taught for 3 years. In 1874, Uncle Will introduced Beaux to a printer and she was offered her first professional illustration assignments, including a commission to illustrate fossils for a book on paleontology. In 1876, she would have attended the Centennial Exhibition in Philadelphia, and was most likely inspired to enroll in additional art instruction of her own.

Although Beaux denies it in her autobiography (interesting, that in 1930, after a long successful life in international art circles, she would still feel the need to defend her propriety), in 1876, the new PAFA building was completed and 21 year-old Celia Beaux enrolled in the antique, costume and portrait classes.

Why the reversal for Uncle Will? For one, his fortunes had turned around and by 1876, there was plenty of money for more art classes for Beaux. Perhaps Uncle Will saw her as a more serious artist with professional potential, or perhaps Beaux was one of those insistent young women who finally wear down their father figure. Beaux even signed up for the life drawing class with the famous instructor Thomas Eakins, but only attended once. (I’ll bet she didn’t mention that to Uncle Will.) By this time, the women of PAFA were allowed to draw and paint nude models, although male models were required to wear a loincloth.

Alice Barber Stephens, The Women’s Life Class (illustration for William C. Brownell, “The Art Schools of Philadelphia, Scribner’s Monthly 18 Sept. 1879)

Beaux claimed that she avoided Eakins’ class because of Uncle Will’s “chivalrous and Quaker soul,” but in truth she might have quickly realized in just one session that Eakins’ life class was ripe for rumor and scandal. Although Eakins was greatly admired by many of his female students and has since been recognized as one of the most progressive teachers of the era with his emphasis on anatomy and the live human form, he would be forced to resign his PAFA teaching post in 1886 amidst allegations that he encouraged the female students to pose in the nude, that he exposed himself to a female student, and that he lifted a loincloth from a male model in the women’s life class.

Beaux only pursued her studies at PAFA for a couple of years. It is possible that her uncle, who had been generously supporting her studies, decided that two years was enough. It’s also possible that life just got in the way, as it is known to do. These years were a time of courtship for Beaux and her older sister, which brought its social and domestic distractions.

When Beaux’s older sister Etta married Henry Sturgis Drinker in 1879 and Beaux had no acceptable offer of her own, Beaux turned back to art classes. Or perhaps it is more accurate to say that Beaux found no man who was more interesting than her art.

This time she would study china painting, a popular decorative craft that would have given Beaux something from which to make a living. After lessons at the National Art Training School of Philadelphia, she started to make money painting portraits of children on porcelain plates. She gave it a try for awhile but kind of hated it: “I remember it with gloom,” she admitted in her autobiography. From the image below, you can tell that Beaux’s ability to get a likeness is developing, but that her subject appears utterly joyless. (Then again, maybe he was a joyless little snot and she nailed it.)

Cecelia Beaux, Child on Porcelain Plaque (1880), Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (not on display)

Beaux’s Turning Point: Life Classes

The turning point for Beaux came in 1881, when at the age of 26 a friend from her early days at the Lyman School invited her to join a life drawing and painting class supervised by William Sartain, a French-educated artist and successful New York professional. It would be the first time Beaux would ever take classes with a live model. She clicked with Sartain’s gentle style. Beaux began painting portraits with confidence and inspiration. Her work took a huge step forward.

When Beaux wrote about her first life classes 50 years later, you can just feel the powerful impact the experience had on her:

… the unbroken morning hours, the companionship, and, of course above all, the model, static, silent, separated, so that the lighting and values could be seen and compared in their beautiful sequence and order, all this was the farther side of a very sharp corner I had turned, into a new world which was to be continuously mine.

Sartain was one of those rare artists who was also a magnificent teacher. Beaux describes his ability to communicate his vision:

What I most remember was the revelation [Sartain’s] vision gave me of the model. What he saw was there, but I had not observed it. His voice warmed with the perception of tones of color in the modeling of cheek and jaw in the subject, and he always insisted upon the proportions of the head, in view of its power content, the summing up, as it were, of the measure of the individual.

This ideal, the most difficult to attain in portraiture, is hidden in the large illusive forms; the stronger the head, the less obvious are these, and calling for perception and understanding in their farthest capacity.

When our critic rose from my place and passed on, he left me full of strength to spend on the search, and joy in the beauty revealed; what I had felt before in the works of the great unknown and remote now could pass, by my own heart and hands, into the beginning of conquest, the bending of the material to my desire.

What moxy! Beaux’s world had just exploded with confidence and inspiration. She would soon begin her own conquest of the art world, “bending material to her desire.”

Cecelia Beaux’s Portrait Career is Launched

It was about this time that Beaux rented her own art studio on Chestnut Street in Philadelphia (at first shared with cousin Emma Leavitt) and began painting portraits in earnest. The PAFA Archives contain some interesting photographs of the cousins in their studio in the 1880s.

In 1883, Beaux found herself in the “large barren studio” with tall ceilings and full light, dreaming of a large picture. She began to sketch a composition in the style of Whistler’s famous Arrangement in Gray and Black #1: Portrait of the Artist’s Mother (1871), which she would have seen at the Centennial Exhibition of 1881. Beaux’s sister agreed to pose for the oversized canvas along with her wiggly 3 year-old son. She claims that “the presiding daemon spoke French in whispering the name of the proposed work”: Les Derniers Jours D’Enfance. Even if you don’t speak French you can still somehow understand “the last days of infancy” and the bittersweet intimacy that conveys.

Celia Beaux, Les Derniers Jours d’Enfance (1883-5), oil on canvas, 46 x 54, Pennsylvania Academy of the Arts

It took Beaux two years to finish the double portrait. She had never before done anything but heads. Here she had to figure out not only the full body, but the interaction of the two, as well as a background, table and flowers. And then the rug, which is way more difficult than it looks. (I know, I’ve tried it. My needlepoint rug looked great, but completely overpowered the rest of the painting.) It was ambitious to say the least. She received regular criticism from her former teacher William Sartain, who stopped by her studio whenever he could get away from New York, but other than that, she kind of figured it out on her own. She was 30 years old when she entered it into the Annual Exhibition of the Pennsylvania Academy and won the Mary Smith Prize for the best painting by a female artist.

Now she was on a roll. She would soon complete Ethel Page as Undine (1885) — again, on her own in her own studio without dedicated instruction — and would win the Mary Smith Prize at the Pennsylvania Academy for the second year in a row. Beaux would work on over 40 portraits in the next few years, seeking to distinguish herself as a serious professional and not a dilettante, much like Mary Cassatt did in France.

Celia Beaux, Ethel Page as Undine (1885), oil on canvas, private collection

The Paris Salon

Beaux’s biggest triumph as an up-and-coming artist would come in 1887 when her friend and fellow artist Margaret Lesley Bush-Brown offered to take Les Derniers Jours d’Enfance to Paris and to submit it to the Paris Salon on Beaux’s behalf. Bush-Brown was a friend from PAFA who had studied in Paris at Académie Julian with Jules Lefebvre and Gustave Boulanger, as well as Carolus-Duran and Jean J. Henner. Bush-Brown carried the painting on the top of a cab to the studio of Jean Paul Laurens for his advice. Laurens urged Bush-Brown to send it to the Salon. Despite Beaux’s lack of connections in the Paris art world, it was accepted. As Beaux said in her autobiography:

It had no allies; I was no one’s pupil, or protégée; it was the work of an unheard-of American. It was accepted, and well hung on a centre wall. No flattering press notices were sent me, and I have no recorded news of it. After months it came back to me, bearing the French labels and number, in the French manner, so fraught with emotion to many hearts.

Beaux describes how she sat and stared at her painting when it was returned to her in Philadelphia, resolving to go to Paris herself to continue her studies.

I sat endlessly before it, longing for some revelation of the scenes through which it had passed; the drive under the sky of Paris, the studio of the great French artist, where his eye had actually rested on it, and observed it,. The handling by employés; their French voices and speech; the propos of those who decided its placing; the Gallery, the French crowd, which later I was to know so well; . . .

But there was no voice, no imprint. The prodigal would never reveal the fiercely longed-for mysteries. Perhaps it was better so, and it is probable that before the canvas, dumb as a granite door, was formed the purpose to go myself as soon as possible.”

Next Post: Celia Beaux in France

Sources and for Further Reading:

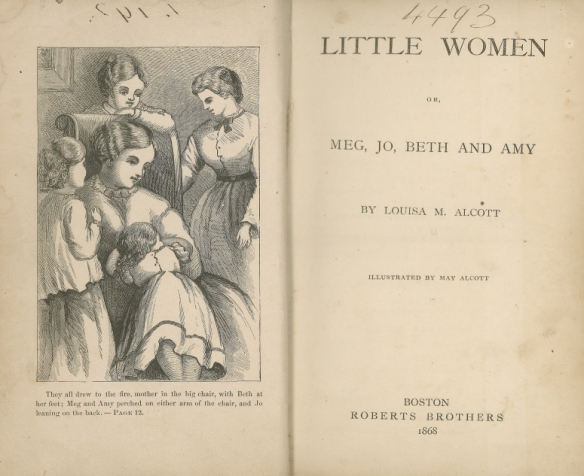

Cecilia Beaux, Background with Figures, Autobiography of Cecilia Beaux, Houghton & Mifflin Co. (1930)

Alice A. Carter, Cecilia Beaux, A Modern Painter in the Gilded Age, Rizzoli (2005) – although note the book cover which appears below curiously says “Victorian Age.” My copy, and I am looking at it right now, clearly says “Gilded Age.”

Sylvia Yount, et. al. Celia Beaux, American Figure Painter, High Museum of Art, Atlanta (2007), accompanying the 2007-8 exhibit by the same name at the High Museum of Art, Atlanta Georgia, The Tacoma Art Museum, Tacoma, Washington and the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

Cecilia Beaux: A Modern Painter in the Gilded Age by Alice A. Carter

You must be logged in to post a comment.