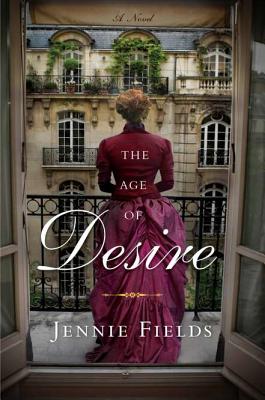

I just finished The Age of Desire by Jennie Fields, and I couldn’t wait to get back to Paris to play “Edith For A Day.”

The Age of Desire is the fictionalized story of Edith Wharton’s steamy mid-life extramarital affair with Morton Fullerton between the years of 1907-1910. It’s not just another imagined love story, this novel is based on Edith Wharton’s own letters, which Morton Fullerton saved and which are now housed in a collection at the University of Texas.

Edith Wharton’s life in Paris was one of upper-crust privilege, governed by strict rules of propriety. But these private letters show that she still found a way to carve out space for another secret life, one that was free, defiant and passionate. It’s a great story – who doesn’t wonder how Edith, such a grand dame of New York high society, could become so unhinged by an unreliable, bisexual American boulevardier?

Let’s walk in her footsteps and see where she pursued this double life. Follow along on my Edith Wharton Tour on this Google Map.

Edith Wharton arrived in Paris in the winter of 1907 along with her wet-blanket husband Teddy and her long-time secretary Anna. Edith was 45 years old and had recently published The House of Mirth. As Edith herself later said in A Backward Glance, she was looking for a flat in Paris so she could “see people who shared my tastes.”

And Edith had good taste. The Whartons rented a Left Bank apartment owned by George Vanderbilt. As Fields said in Age of Desire:

Edith was enamored the moment she stepped in to visit George a few seasons ago. It boasts all the Faubourg’s most ravishing touches: high ceilings, exquisite boiseries and elegant moldings. George’s oriental vases and lush Aubusson carpets only make it more elegant.

The Vanderbilts obviously had a good sense for real estate. The townhouse came with its own staff, although the Whartons also hired their own local bonne. The top floor featured a common room where the servants gathered in the evening.

You can visit 58 rue de Varenne, but you can’t get inside. It is now a carefully guarded annex to the Prime MInister’s office, which is across the street in the Hotel Matignon.

58 rue de Varenne, Edith Wharton’s first apartment in Paris (1907-1909). Rented from George Vanderbilt. Currently an annex of the Prime Minister’s office across the street in Hotel Matignon. The day I went to visit, the doorway to the courtyard was open but I was quickly chased away. The guard thought I was crazy when I told him L’Americaine Edith Wharton used to lived there. “Non, le PM!”

After the guard escorted me out of the courtyard and back onto the sidewalk, he did allow me to take this photo looking back into the courtyard. Can you picture Edith back there, greeting Henry James or Morton Fullerton at the door?

Edith enjoyed her social life in the Left Bank world of teas and salons. She was good friends with the French author Paul Bourget, who lived around the corner with his wife Minnie on rue Barbet de Jouy.

Edith loved attending the Tuesday night salons of the widowed Comtesse Rosa de FitzJames at 142 rue de Grenelle, which is now the Swiss Embassy. In fact, it was at Rosa’s salon that Edith first met the roguish Morton Fullerton.

You can tell that Jenny Fields had fun playing with the attraction between Edith and Morton in Age of Desire. At their first meeting, Morton told Edith that he’d read and enjoyed The House of Mirth, and impressed Edith by asking about Lily Bart. Nice ice breaker for a writer, right? When they discovered they were mutual friends of Henry James, Edith was definitely intrigued. She couldn’t wait to see Morton again.

But Edith would have to wait. Discretion prevailed. When Henry James came for an extended visit at Edith’s, Morton dropped by as often as he could. Edith and Morton finally had a private get-to-know-you walk through Edith’s posh Left Bank neighborhood, “the sun . . . splash[ing] itself all along the high-walled hotel particuliers of the rue de Varenne.”

In the pages of Age of Desire, Edith and Morton strolled down to the nearby lawns of Les Invalides. When they sat down in a nearby garden, things really started to buzz:

In the garden, they locate a bench and sit side by side. She can sense his body heat, and takes in his odor of driftwood and lavender. Edith feels something she hasn’t felt in a long time and cannot name. . . .

[Morton says,] “See that honeybee?” On the hedge behind them, a honeybee as far as a blackberry is trying to wedge himself greedily into the narrow trumpet of a pink flower. Fullerton turns his gaze to her and says, “That’s how drawn I am to you.”

Really, Morton, you little devil. No more Age of Innocence for Edith.

Square d’Ajaccio near Les Invalides in Paris. I could easily picture Edith and Morton on one of those benches. It was a pretty romantic park in real life. One amorous couple kissed shamelessly on a bench while another were entangled in the grass. Ah, Paris!

Unfortunately, Edith’s newfound passion would have to wait some more. The Whartons returned each spring to their palatial home (The Mount) in Lenox, Massachusetts, and would not return to Paris until December, 1907.

Edith and Morton’s relationship finally escalated the next season in Paris. They snuck off on long walks through Montmartre, the Tuileries, and Luxembourg Gardens. They met at the Louvre, took daring trips in her car. Their love become ostentatious; people took notice. But Edith didn’t care. How can a woman say no to those little green boxes of macarons framboise from La Durée?

“Instead of flowers, [Morton] proffers a pale green box of gleaming pastel macaroons from Laduré, the pastry shop on Rue Royale.”

“It’s just like my brother to choose to live in Paris but reside on a street called American Place,” she says.

“Ah yes [says Morton]. Sophisticated Mrs. Wharton wouldn’t be caught dead here . . . and yet here you are!”

A lovely old residence on Place Etat-Unis, a beautiful square in the 16th arrondissement where Edith’s brother Harry Jones lived. Yes, it’s true, a lot of Americans lived there and still do. In this scene in the novel, Fields does a great job of capturing Edith’s Left Bank snobbery.

Edith may not have cared for her brother’s neighborhood, but she adored staying at the Hotel Crillon on La Place de la Concorde. She often checked herself into the Crillon in before or after the Vanderbilt place was available. In April 1909, Edith tucked herself into the Crillon and worked on her next novel, Custom of the Country. Edith’s affair with Morton was sputtering at the time, and according to Age of Desire, she refused to have a secret rendezvous with him at the Crillon, no matter how strong his hints.

The folks at the Crillon’s boutique were good sports and let me take this photo of a Hotel Crillon bathrobe. I was trying to picture Edith in a robe and slippers, scribbling away about Undine Spragg’s time in Paris, but that got a little weird.

Even if you can’t swing a month at the Crillon like Edith, you can still enjoy a nice Sancerre on the terrace.

By 1909, Edith has decided to find a place of her own in Paris. Both her marriage and her relationship with Morton are troubled, but she can at least find happiness abroad.

Edith lands on the perfect apartment at last. And to think it’s just across the street from the Vanderbilts’ on the Rue de Varenne. But bigger, and newer, with its own guest suite and servants’ quarters and steam heat! Unheard of in Paris. And what makes it so extraordinary is that the rooms are luxuriously spacious and overlook a small but elegant garden. A garden! It’s all she could want in space and light. Precisely in the part of the Faubourg she loves.

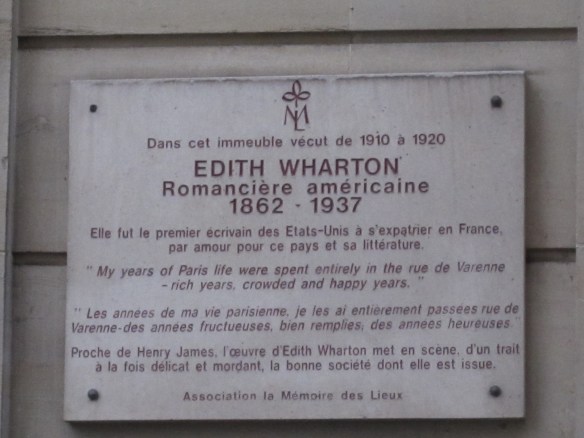

The plaque at 53 rue de Varenne commemorating Edith Wharton’s years here (1910-1920), her love for France and her friendship with Henry James.

The carriage door was open, so I was able to walk inside toward the courtyard and glimpse a peek of the lovely tiled lobby of Edith Wharton’s former townhouse at 53 rue de Varenne.

The view of the back of Edith Wharton’s apartment at 53 rue de Varenne, which overlooked beautiful private gardens. Look again at the cover of Age of Desire. Looks like Edith could be standing right there, doesn’t it?

Fouquet’s on Champs Elysée. You can have a perfectly pleasant (although pretty expensive) dinner there, unlike the miserable dinner Edith and Morton had toward the end of the book!

If you find yourself in Paris and would like to have your own Edith Wharton Day, just follow along on my Google Map. I would recommend starting at the Rue de Bac Métro stop, walking down the rue de Varenne, and then heading over to Les Invalides. From that point you can walk across the Seine or hop back on the Métro to get to the Crillon, La Durée and Fouquet’s. After some macaroons from La Durée, a glass of wine at the Crillon and dinner at Fouquet’s, you’ll definitely feel spoiled, and perhaps, a little like Edith.

Age of Desire is an entertaining treat for Edith Wharton fans, but is also a good read for those who haven’t yet read her work. Be prepared, though, because after you read Age of Desire, you could end up spending the next month holed up in a chair, getting nothing else done, reading or re-reading all of Edith Wharton’s marvelous novels and stories. To those purists who object when their favorite literary icons are injected with thoughts and actions from another author’s imagination, I say just give it a try. Play along.

Jennie Fields does a fabulous job following Edith and Morton through Paris and beyond. In the course of her research, Jennie visited Herblay, Senslis and Montmorency, some of the towns outside Paris to which Edith and Morton snuck off to for their trysts. Field’s research pays off. I thought it was beautifully imagined and very well researched. It’s definitely a recommended read.

Related articles

- Edith Wharton and Friends in Vogue (vol1brooklyn.com)

- ‘Age Of Desire’: How Wharton Lost Her ‘Innocence’ (wnyc.org)

- Vogue Dressed Up Jeffrey Eugenides and Junot Diaz for an Edith Wharton Spread [Mag Hag] (jezebel.com)

- Is Edith Wharton the New Jane Austen? (blogher.com)

You must be logged in to post a comment.