Where The Light Falls by Katherine Keenum is a lovely painterly novel set in late 19th century Paris. What a perfect book for a review and literary tour by The American Girls Art Club in Paris.

You can find various sites in the book on Where the Light Falls Literary Tour in Google Maps.

The story begins when a young artist named Jeannette Palmer gets expelled from Vassar College for helping her roommate elope. Despite her public shaming, Jeannette talks her prominent Ohio family into supporting further art studies in Paris.

Jeannette and her chaperone, a “spinster” cousin, find lodging in a pension on rue Jacob on the Left Bank, while Jeannette enrolls in the women’s drawing class at the Académie Julian. Had Jeannette arrived in Paris a decade or so later, she could have easily been one of the lodgers at The American Girls Art Club in Paris, which opened its doors in 1893. Instead, Jeannette would be one of the first-wave trailblazers of American women artists to journey to France.

Jeannette’s story is loosely based on the life of the author’s own great-grandmother, who was indeed expelled from Vassar College and who traveled to Paris to study art with Carolus-Duran. Because no journals, letters or memoirs survived, Katherine Keenum had to rely on her imagination to tell her great-grandmother’s story.

Keenum’s research is considerable, but it feels like a natural part of the story. When Jeannette is learning from such famous masters as William-Adolphe Bouguereau or Carolus-Duran, you feel like you’re there too. Keenum places Jeannette in Paris at a turning point in the history of art; it is remarkable how much Jeannette and her cousin Effie get to witness in just two years.

One of Keenum’s primary sources for the life and times of an American art student abroad was Abigail May Alcott Nieriker’s guidebook for women artists called Studying Art Abroad and How to Do it Cheaply (1879), which describes May’s studies at Académie Julian, her approach to life in Paris, and her travels throughout France. (In a previous blog post here called Little Women in Dinan, France, I wrote about May and her famous sister’s travels abroad.)

Jeannette begins her studies at the Académie Julian, a private art school which welcomed women into segregated studios, unlike L’Ecole des Beaux Arts. The first women’s atelier at Académie Julian was located in the Passage des Panoramas in the 2nd arrondissement of Paris. This Paris Passage still stands today – it it a lovely historic covered mall at 11 Boulevard Montmartre.

In Chapter 8, Jeannette has a hard time finding the stairs that led to the second floor studio of the Académie Julian. Keenum describes a set of service stairs along one of the transverse passages, but on my various visits to the Passage des Panoramas during my year in Paris, I was never able to find them. I could see a second floor under the peaked glass ceiling, I just couldn’t get there. I’d love to hear from any of my followers to see if they’ve ever managed to gain access to the second floor of the Passage des Panormas, or if it’s a place that belongs only to the past.

An old sign inside the Passage des Panoramas in the 2nd arrondissement of Paris, the location of Académie Julian’s first atelier for women in the 1870s. You can still walk through the Passage today for a sense of the 19th century.

An interior view of the Passage des Panoramas. In Chapter 8, Keenum describes it like this: “Inside, restaurants and small specialty shops crowded both sides of an arcade. Painted signs hung out at right angles overhead like banners; a tiled mosaic floor ran for two blocks. Above a second story of shops, the whole length was roofed with a peaked ceiling of glass.”

Marie Baskirtsheff, In The Studio (1881). A painting of the women of Académie Julian by one of its most famous students. Although the women were allowed to paint from live nude models, this painting avoids controversy and shows a draped figure of a young boy. Dnipropetrovsk State Art Museum, Ukraine. In Chapter 8, one of Jeanette’s classmates points out their fellow student “The Countess,” [Countess Marie Bashkirtseff] “a star student in the class for the full nude.” The Countess is supposedly picture in the center of this painting with the palette in her lap.

A photo of one of the women’s classes a Académie Julian. It is undated, so it is possible it is from the other women’s atelier which opened in the 1880s on rue de Berri near the Champs Elysée. Source:http://verat.pagesperso-orange.fr/la_peinture/Mixite_Beaux-Arts.htm

A photograph of some of the female messiers (studio assistants) of the Académie Julian. Source:http://verat.pagesperso-orange.fr/la_peinture/Mixite_Beaux-Arts.htm

William-Adolphe Bouguereau, Self-Portrait (1879). Bouguereau was a famous 19th century Salon artist who provided private instruction for both men and women at the Académie Julian. He would be engaged to one of his American students, Elizabeth Jane Gardner, for 17 years. They would finally marry in 1896 after the death of his mother, who strongly disapproved of the match.

The Académie Julian still stands today on the rue du Dragon in the 6th arrondissement of Paris. This was originally one of the men’s ateliers, but has long accepted both men and women.

Jeannette enjoys her studies at the Académie Julian under William-Adolphe Bouguereau, but really, Bouguereau only passes through the class a couple of times a week with a few comments like pas mal, pas mal. Although she’s making friends with her fellow art students from around the world and learning all about the Paris art world, Jeannette couldn’t help but aspire for better art instruction.

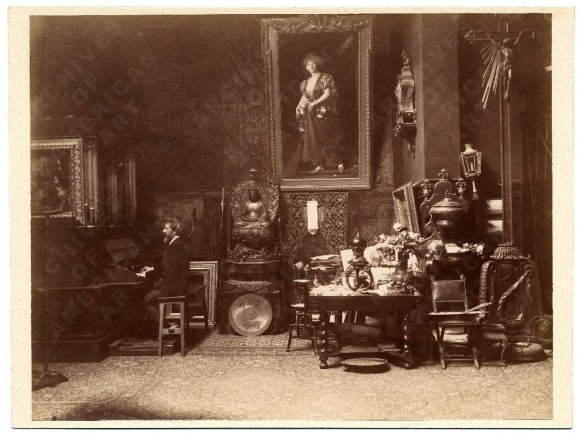

Jeannette gets her big break when she makes the acquaintance of Carolus-Duran through a wealthy friend of the family who is having her portrait done. Duran invites Jeannette for a studio visit at 58 rue Notre Dame des Champs. When Jeannette and Effie arrive at his address, they quickly realize what a celebrity painter he is. There are three carriages at the curb and a servant to greet the guests. Effie gushes: “Why, it’s as elegant as a hotel lobby or a fashion house!”

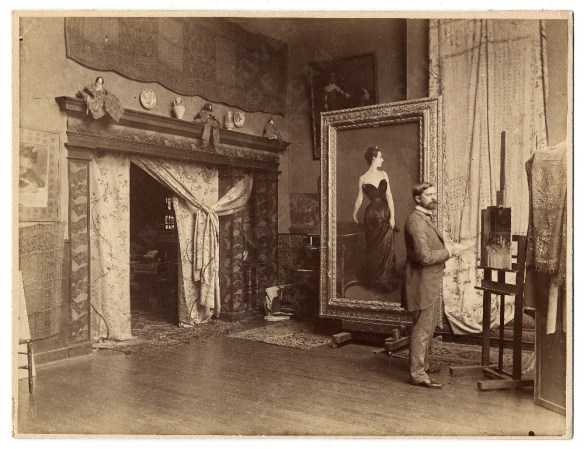

A photo of Carolus-Duran playing the organ in his art studio (1885). From the digital image gallery at the American Archives of Art called “Photographs of Artists in their Paris Studios (1880-1890).” Keenum gets it right when she describes the studio as being “strewn with thick Persian rugs and hung with tapestries and pictures.”

Rue Notre Dame des Champs, a narrow winding road through Montparnasse which earned the title “the royal road of painting” because of all the famous French artists who lived there, including Bouguereau, Courbet and Carolus-Duran.

Carolus-Duran invites Jeannette to join his women’s painting classes at 11 Passage Stanislaus in Montparnasse. Passage Stanislaus is now known as rue Jules Chaplain, a small street just off of rue Notre Dame des Champs.

Jeannete struggles to find the extra money to enroll in Carolus-Duran’s classes, but once she does, she gets to observe one of the true masters of the art. One of my favorite scenes in the book is in Chapter 30, when Carolus-Duran pulls Jeannette right up next to him to demonstrate the essence of portrait painting:

Study where the light falls and where the shadows lie. We commence by indicating the darkest masses. . . .

Either way, what is most important now is to find the demi-teinte generale. Half close your eyes, mademoiselle; regard the model.

It’s enough to make you want to find a model and set up and easel right now, isn’t it?

Jeannette is in the perfect place and time to witness art history. She meets a young John Singer Sargent, a fellow student in Carolus-Duran’s men’s atelier who would have been only 23 years old at the time. Jeannette and her classmates celebrate when Sargent’s portrait of Carolus-Duran wins an Honorable Mention at the Paris Salon of 1879.

John Singer Sargent’s portrait of Carolus- Duran (1879), Clark Art Institute, Williamston, Massachusetts. When Jeanette meets John Singer Sargent at a garden party, she says: “I hear your portrait of Carolus is wonderful.”

There are plenty of other moments in art history that Jeannette gets to be a part of, including the Fourth Impressionist Exhibit of 1879, where she sees and critiques Mary Cassatt’s Little Girl in a Blue Arm Chair (1878):

That grumpy little girl sprawled on the aqua-blue chair – well, she’s vivid, but all that other aqua furniture climbing to the ceiling, . . . it’s hideous!

Don’t blame Jeannette. Most of the world wasn’t yet ready for the Impressionists either.

It is an incredible time in the history of art, and Jeannette is it the middle of it all. What a wonderful way for Katherine Keenum to honor the memory of her great-grandmother, who really did have a chance to be a part of history. In ways we can only imagine.

Where the Light Falls by Katherine Keenum: Highly recommended.

Where the Light Falls Literary Tour: As created by The American Girls Art Club in Paris.

You must be logged in to post a comment.