Mary Cassatt was an American painter who lived in most of her life in France. If you’re curious about Mary Cassatt’s years in Paris during the 1870s and 80s, and would like to see photos of the different Paris apartments in which she and her family lived, click here for a prior post.

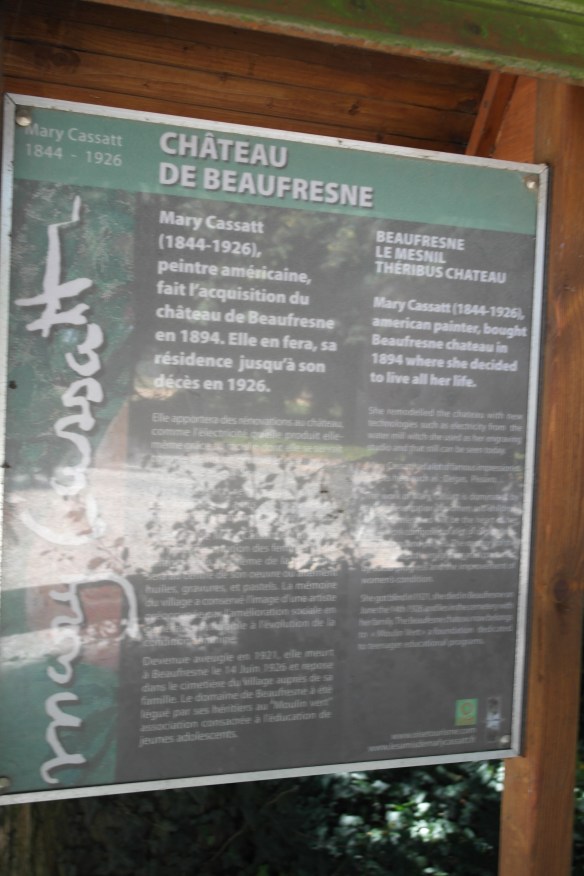

But it turns out there is much more to Cassatt’s story than Paris. Cassatt led a long productive life, and spent much of her time in summer homes in the country. In fact, from 1894 until her death in 1926 Cassatt lived in a summer home in Le Mesnil-Theribus, France, a country village north of Paris. Her home was called Chateau de Beaufresne (“Beautiful Ash”) named for the large ash trees that grow in the area. I was lucky enough to visit this beautiful old chateau, which is currently owned by Le Moulin Vert, a group that provides horticultural education for troubled teens.

At the time of my visit, efforts were underway by a group called Les Amis de Mary Cassatt to purchase the chateau and turn it into a museum. I think it’s a spectacular idea. The home and grounds could be as popular as Monet’s in Giverny and the Van Gogh sites in Auvers-sur-Oise. Le Mesnil-Theribus is located about an hour north of Paris on the way to Beauvais, several miles west of A16.

I made arrangements to meet with Marianne Caron, a member of Les Amis de Mary Cassatt, who shared with me many local legends and stories of fellow villagers whose ancestors had known Cassatt. She was a wealth of information.

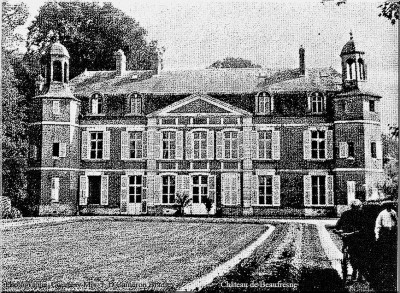

Chateau de Beaufresne, Le Mesnil-Theribus, France. Currently home to Le Moulin Vert, a horticultural program for troubled teens.

In 1893, Mary Cassatt learned that Chateau Beaufresne was for sale. She had been renting another beautiful country home in nearby Bachivillers during the summers of 1891 and 1892, when the owner told her he wouldn’t be renting it out anymore. Cassatt was determined to stay in the area, and made the impulsive decision to buy the Chateau Beaufresne, despite the fact that it needed many repairs.

Chateau Beaufresne (source: http://cassatt.eu)

Cassatt spent most of the summer of 1894 renovating the old chateau. In a letter to Paul Durand-Ruel, she expressed her frustration and told him she intended to sell the house, that it was just too much trouble:

We are finally settled here and, even before we came, I had had enough of my role as landlord; I have given nearly three months of my time and I know that I still have a part of the summer to devote to giving orders, and I ask myself when will I find the time to do a bit of painting! Madame Aude [Durand-Ruel’s daughter and Cassatt’s neighbor in the Chaumont-en-Vexin area] knows the landowners of Trie, would she be so kind as to tell them I am putting Mesnil-Beaufresne up for sale?

The house is very good, very sound. I had water &c put in, Indeed I cannot say that everything is not well, but I do not want to give any more orders to workmen, who don’t follow them anyway.

. . .

What I want is the freedom to work. My mother is no longer of the age or the strength to concern herself with the outdoors, and I don’t have the interest.

My brothers will surely laugh at me, but I won’t say anything until I have sold it and won back my freedom. Certainly it is the best thing in the world.

I am completely fed up with the trouble I had to get a bit of work done (Mary Cassatt to Paul Durand-Ruel, Summer 1894).

What emerges so strongly from that letter is Cassatt’s burning desire to get back to work on her painting. Doesn’t she sound like a 21st century woman, frustrated with all of the distractions and obstacles that stand in the way of our freedom? In any event, Cassatt changed her mind about selling the house. Soon she is working away at her painting and pastels. In another letter to Durand-Ruel, Cassatt says:

I am now settled here for the summer and working hard. I hope to submit to you some pastels before long; if I were a landscape painter, I would [have] no trouble in seeking beautiful subjects – The country looks lovely not withstanding the drought – . . . (Mary Cassatt to Paul Durand-Ruel, May 19, 1896).

Indeed, the property is very lovely, and would be the ideal setting for a landscape painter.

The view of Chateau Beaufresne from the back of the property, across a lovely little pond full of cat tails and lily pads.

The grounds of the chateau include a brook and acres of weeping willows and pond vegetation. It was hard to get the lighting right for a photograph, but it would have been a picturesque place to set up an easel for some plein air painting.

At the back of the property there still stands the small mill that Cassatt used as her printing studio. She would spend as much as 8 hours a day working here.

The sunny room at the back of the chateau that was known as the gallery. It is supposedly where Cassatt used to paint. Imagine that.

A framed photo on display in the chateau shows a car and a donkey cart parked outside the back door in front of the gallery. Note the window treatments that Cassatt used to control the amount of light entering her gallery.

A view of an interior room of the chateau with curved walls and a fireplace. Various old photographs of Mary Cassatt are displayed on the walls. The room is currently used for meetings and conferences.

A commemorative plaque that has been placed along a walk leading from the parking lot up to the front entrance of the chateau.

After Cassatt’s death in 1926, Cassatt’s niece Ellen Mary Cassatt Hare (daughter of Cassatt’s brother Joseph) and her family continued to use the home for summer visits from Pennsylvania, and they continued to employ a small staff to tend to the home in their absence. At sometime toward the end of World War II, General DeGaulle spent one night at the chateau on his way from London to Paris (Encyclopedia Picardie). The chateau fell into disrepair and in 1961 was donated to Le Moulin Vert, a social service agency of L’Oise region.

Ever since my visit to the chateau, I have enjoyed checking out Cassatt’s paintings to detect a hint of the chateau or its grounds in her work. Check out the beautiful window scene in the background of this one, Children Playing with a Dog (1907). Perhaps?

For further reading: Cassatt and Her Circle: Selected Letters, ed. Nancy Mowll Mathews

You must be logged in to post a comment.