The American Girls Art Club, which once stood at 4 rue de Chevreuse on the Left Bank of Paris, is now known as Reid Hall, and is owned by Columbia University’s Global Centers Program.

The property was built by the Duc de Chevreuse and way back in the 18th century it housed the Dagoty porcelain factory. In 1834, the site was turned into a Protestant school for boys called the Keller Institute.

In the early 1890’s, Elisabeth Mills Reid, a wealthy American philanthropist and wife of the American ambassador, got the idea to start a residential club for American women artists in Paris. She knew about an arts club for men on the rue Paul Séjourné, and when she learned that the Keller Institute property was available, she got together with her friends, Reverend and Mrs. William Newell. The Newells were evangelicals who had been hosting Sunday evening social hours for American girls at their own home on the rue de Rennes. With the help of the Newells and the larger expatriate community in Paris, Elisabeth Reid established The American Girls Art Club in Paris, a residential club for young American women artists that provided matronly supervision and spiritual guidance.

The club thrived because it was affordable and very social. There was room for approximately 40-50 women in either single or double rooms at approximately $30 per month. There was a “dainty blue” receiving room for playing the piano and serving tea, as well as a reading room full of English-language books and magazines. The residents often strolled and sketched in the gardens of the courtyard. Each Sunday the Newells arranged an informal religious service followed by a social hour. The club hosted an elaborate Thanksgiving dinner every year.

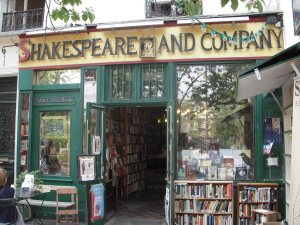

The club was within walking distance of the Luxembourg Gardens, L’Ecole des Beaux-Arts, and many bookshops and restaurants along Boulevard Raspail. Although the female residents could not study at L’Ecole des Beaux Arts until 1897, many of them did study at prominent private ateliers in Paris, including the studios of Bouguereau, Whistler and Carolus-Duran.

The residents planned and hosted their own art exhibits at the club, inviting their fellow students and art teachers. In 1895, they formed the American Woman’s Art Association of Paris to host the annual show. Mary Cassatt, Mary Fairchild MacMonnies Low and other prominent women artists who were permanent residents of Paris helped preside over the club, serving as jurors and officers. Prominent Paris artists and art teachers attended the exhibitions, providing the members with valuable critiques and praise. Each year, the Art Club purchased one piece of art from the exhibition for display in the Club.

Anne Goldthwaite’s 1908 oil painting of the courtyard of the American Girls Art Club in Paris is in the collection of the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York. Take a peek at it here.

During World War I, the property became a hospital, and was held by the American Red Cross until 1922. Elizabeth Reid and her daughter-in-law then arranged for it to become Reid Hall, an association for American college women abroad. Gertrude Stein even made an appearance in 1931 at the invitation of one of Reid Hall’s art students.

In 1964, Reid Hall was bequeathed to Columbia University. Since then, it has been part of a network of international study programs. Since the time I founded this blog, Reid Hall has updated its website to include a great deal of information about the history of the building, including its time as the American Girls Art Club. For great historical photographs, a timeline and lists of women artists who lived, worked or visited the club, you can read more here. You could click their website around all day, it’s fascinating stuff.

The unassuming front entrance to 4 rue de Chevreuse, the home of The American Girls Art Club in Paris from 1893- 1914.

The view of the Reid Center outside toward the courtyard. Toward the back is a high wall that borders rue de la Grand Chaumiere, a street that is still full of art studios today. The lodgers could take a shortcut to their classes at nearby Académie Colarossi by exiting through a gate in this wall.

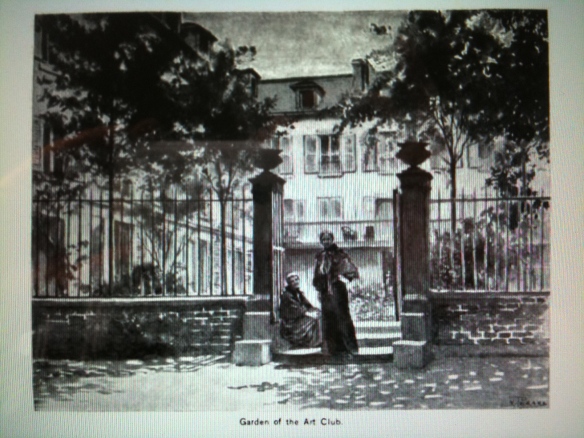

Few paintings or sketches of the American Girls Art Club remain, although I was able to find this rendering in a scholarly journal.

The garden of the American Girls Art Club, artist and date unknown. Source: Woman’s Art Journal Vol. 26. No. 1 (2005)

Sources: http://www.ReidHall.com and Woman’s Art Journal Vol. 26, No. 1 (2005)

You must be logged in to post a comment.