Author Archives: americangirlsartclubinparis

Wine and War in France

Wine and history pair up well together, especially in France. More than anywhere else, the story of French winemaking is a lesson in history and tradition. Some French families have been making wine for dozens of generations. Don & Petie Kladstrup’s book Wine & War tells the story of how some of these families survived the two great wars of the 20th century. It makes for fascinating reading whether your interest is in history or more toward the wine. And if like me, you like both, it’s a must read. It makes a perfect companion for a wine tour in France.

Wine & War focuses on four French winemaking families: The Drouhins in Burgundy, the Hugels in Alsace, the owners of Lauren-Perrier in Champagne, and the Miaihles in Bordeaux. These are still some of the most prominent wine producers in France today. Their stories are triumphant and gripping, often involving deceit, risk and resistance in their battles to save their family legacies from theft and ruin by the Germans. In many cases, the winemakers even had to fight for their lives.

On my recent travels through Burgundy and Alsace, I brought along my copy of Wine & War and was able to make quite a few connections with the book. Here is a Google Map to save you the trouble of writing down the addresses and directions yourself. Our wine guide Tracy from Burgundy by Request (highly recommended) had read and enjoyed the book, so we were able to discuss some of these sites as we drove from town to town.

Maison Robert Drouhin, Beaune, Burgundy:

Burgundy: Maison Joseph Drouhin has been in the hands of the Drouhin family for the last 130 years. Today, the fourth generation of Drouhins (the great-grandchildren of Maurice Drouhin) maintains the caves at the same location as Maurice did during World War II, at 7 rue d’Enfer in the heart of Beaune. Wine tastings are available and highly recommended!

Burgundy: In one of the most dramatic passages of the book, the Nazis knock at the door to arrest Maurice Drouhin. Maurice has been prepared for this moment, and evades arrest by escaping through his tunnel of wine caves. He comes out of a secret doorway onto rue Paradis, and runs to the Hospice de Beaune just two more blocks away, where he hides out for 10 months.

“Even with a candle and his knowledge of the vast cellars, the darkness made it difficult for [Maurice] to find his way. On one of the four levels of passageways that made up his cellar, he finally found what he was looking for. Maurice brushed away the cobwebs and eased himself behind the wine racks; then he gripped the handle of the door and pulled. It opened easily. Stooping slightly as he went through, Maurice quickly made his way up several steps that led to the street outside,the rue de Paradis, or Street of Paradise.”

Burgundy: Hospice de Beaune. A hospital that owns some of the best vineyards in Burgundy. It has its own labyrinth of caves underground, and that is where Maurice Drouhin was able to hide from the Germans, no doubt with the help and confidence of his friends and fellow winemakers.

Comblanchien, A Village in Burgundy with a Tragic History

Wine & War includes the story of Comblanchien, a small winegrowing village in the heart of Burgundy. It was the center of much of the local Resistance activity. The locals Resistance fighters often sabotaged or blew up the German trains as they passed through on the main line from Paris to Lyon. In 1944, the Germans were on the run, but not before they retaliated against the village that had caused them so much trouble.

On August 21, 1944, the Germans attacked the village of Comblanchien, burning people out of their homes and their church. Eight people were killed, fifty-two houses were burned to the ground, and the church was reduced to a pile of ash. Some were able to survive by hiding in their wine caves while their houses burned above them. Twenty-three villagers were arrested and taken to Dijon for execution. Eleven of them were eventually freed, but the rest were deported to work camps in Germany.

Burgundy: The memorial in Comblanchien for the eight villagers who were killed in the German attack on August 21, 1944. The ranged in age from 72 to 18 years old.

Burgundy: The “new” church in Comblanchien, built to replace the church the Germans burned to the ground in 1944.

Alsace: The Hugel Family of Riquewihr

The story of the Hugel family’s experience in World War II is particularly interesting because of their unique position in Alsace, which was annexed back into Germany in 1939. It had been French ever since the end of World War I, but the Germans returned and changed everything as soon as they could, from the language to the road signs and the even the names of the wine houses. Hugel et Fils became Hugel und Sohne. “If you even said bonjour, you could go to a concentration camp.” The Hugel sons were drafted into the German army, and the Hugels were forced to close their 300 year-old family business because Jean Hugel refused to join the Nazi party. In fact, Jean escaped to a hotel in nearby Colmar where he had pretended to be a member of their staff.

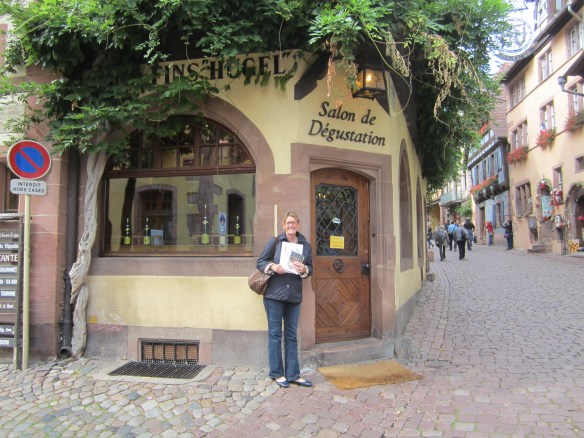

Alsace: Riquewihr, France on the Alsace Route du Vin between Colmar and Strasbourg. An absolutely beautiful town for a day visit.

Here I am geeking out a little bit over the fact that I really did find the Hugel winetasting room. They even had a French copy of the book in their shop.

Wine & War by Don and Petie Kaldstrup: Highly recommended.

Burgundy by Request: Highly recommended.

Note: I received no consideration for this post. I bought my own copy of the book and we paid full price for Tracy Thurling’s full-day Grand Cru wine tour, which we loved.

Napoleon and his Women

I am always thrilled to hear when Michelle Moran has another new book out. After enjoying Madame Tussaud so much just a year or so ago, I was excited to see that Moran has already written another book set in France.

The Second Empress (Crown, U.S. August 2012) is about Napoleon’s short second marriage to 18 year-old Marie-Louise, Archduchess of Austria, after his first marriage to Joséphine Beauharnais ended in divorce. Although Napoleon and Josephine were still in love, Josephine was unable to have any more children. She had married Napoleon at the age of 32, and was already the mother of two teenagers from her first marriage. By the time of Napoleon and Josephine’s divorce in 1810, Josephine was 46 and her daughter Hortense was 27. Napoleon had to have an heir, and within a year of his second marriage, the young Marie-Louise had given birth to their son Napoleon II. Okay, enough history – just wanted to give some background.

The Second Empress is not only about Napoleon and Marie-Louise, but it is also about Napoleon’s strange power-hungry sister Pauline. The chapters told from Pauline’s point of view are ridiculously good. The story alludes to the innuendo of incest between Pauline and Napoleon, which adds an extra creepy layer of intrigue. I also enjoyed the way Moran developed a relationship between Josephine’s daughter Hortense and Marie-Louise. The two women, who were close to the same age, actually learned to like and respect each other. It’s clear that Marie-Louise can’t stand Napoleon, and that all she really wants is to have his heir and get the hell out of France. In the meantime, Napoleon keeps writing love letter to Josephine, who was awarded her beloved Chateau de Malmaison in the divorce.

Last spring I visited Chateau de Fontainebleu and Chateau de Malmaison, two of the homes in which Napoleon and Josephine had lived in the outskirts of Paris. Here are some photos and comments to help you enjoy The Second Empress even more.

The Cour d’Honneur at Fontainebleau, also known as the Cour des Adieux in memory of Napoleon’s farewell speech before his departure to Elba in April 1814.

The Diana Gallery at Fontainebleau, the large ballroom decorated with works depicting the myths of Diana, as mentioned in Chapter 13 of the book. Hortense takes Marie-Louise on a tour of Fontainebleau, and they stop here. Marie-Louise looks out the windows and reflects: “Only twenty years ago Marie-Antoinette walked these paths. I imagine my great-aunt in her flowing chemise, and I wonder if she can see me now . . . . An entire revolution left half a million people dead, and for what? This ballroom is just as lavish, this court just as full of greed and excess. Nothing has changed except the name of France’s ruler, and now, instead of an L on the throne, there is a golden N.”

In the meantime, Josephine is living on the other side of Paris at Malmaison, the home she had found and decorated in 1799, while Napoleon was in Egypt. Napoleon gave Malmaison and all of its contents to Josephine in the divorce. Josephine died there in 1814.

The cedar tree that Napoleon and Josephine planted in 1800 to celebrate his Italian victory at Marengo. It’s called the Marengo Cedar, and it still stands on the grounds today.

I absolutely loved my trip out to Malmaison and took about a million more photos. I feel like I need to spare you from a vacation slide nightmare, otherwise I’d just post them all here. I enjoyed Fontainebleau as well, but there is something much more intimate about Malmaison. If you’re interested in more, you can take your own virtual tour on the Chateau Malmaison website. If you are planning a trip to Paris, I recommend the minivan tour with the folks at Paris Vision, who will take you to Malmaison, Petit Malmaison and the church where Josephine is buried all in one afternoon. Paris Vision also offers a minivan tour to Fontainebleau.

Before you go, whether online or for real, you really should read The Second Empress by Michelle Moran. Definitely a recommended read for French history fans.

Disclaimer: I purchased my own copy of the book and paid for my own tours. I received no consideration for my recommendations. If I like a book I tell you, and the same goes for the tours.

A Day in Paris With Edith Wharton

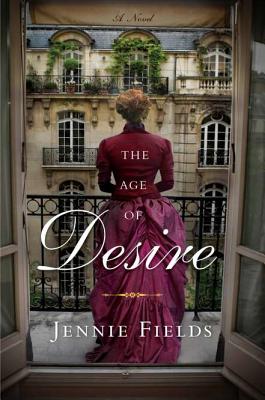

I just finished The Age of Desire by Jennie Fields, and I couldn’t wait to get back to Paris to play “Edith For A Day.”

The Age of Desire is the fictionalized story of Edith Wharton’s steamy mid-life extramarital affair with Morton Fullerton between the years of 1907-1910. It’s not just another imagined love story, this novel is based on Edith Wharton’s own letters, which Morton Fullerton saved and which are now housed in a collection at the University of Texas.

Edith Wharton’s life in Paris was one of upper-crust privilege, governed by strict rules of propriety. But these private letters show that she still found a way to carve out space for another secret life, one that was free, defiant and passionate. It’s a great story – who doesn’t wonder how Edith, such a grand dame of New York high society, could become so unhinged by an unreliable, bisexual American boulevardier?

Let’s walk in her footsteps and see where she pursued this double life. Follow along on my Edith Wharton Tour on this Google Map.

Edith Wharton arrived in Paris in the winter of 1907 along with her wet-blanket husband Teddy and her long-time secretary Anna. Edith was 45 years old and had recently published The House of Mirth. As Edith herself later said in A Backward Glance, she was looking for a flat in Paris so she could “see people who shared my tastes.”

And Edith had good taste. The Whartons rented a Left Bank apartment owned by George Vanderbilt. As Fields said in Age of Desire:

Edith was enamored the moment she stepped in to visit George a few seasons ago. It boasts all the Faubourg’s most ravishing touches: high ceilings, exquisite boiseries and elegant moldings. George’s oriental vases and lush Aubusson carpets only make it more elegant.

The Vanderbilts obviously had a good sense for real estate. The townhouse came with its own staff, although the Whartons also hired their own local bonne. The top floor featured a common room where the servants gathered in the evening.

You can visit 58 rue de Varenne, but you can’t get inside. It is now a carefully guarded annex to the Prime MInister’s office, which is across the street in the Hotel Matignon.

58 rue de Varenne, Edith Wharton’s first apartment in Paris (1907-1909). Rented from George Vanderbilt. Currently an annex of the Prime Minister’s office across the street in Hotel Matignon. The day I went to visit, the doorway to the courtyard was open but I was quickly chased away. The guard thought I was crazy when I told him L’Americaine Edith Wharton used to lived there. “Non, le PM!”

After the guard escorted me out of the courtyard and back onto the sidewalk, he did allow me to take this photo looking back into the courtyard. Can you picture Edith back there, greeting Henry James or Morton Fullerton at the door?

Edith enjoyed her social life in the Left Bank world of teas and salons. She was good friends with the French author Paul Bourget, who lived around the corner with his wife Minnie on rue Barbet de Jouy.

Edith loved attending the Tuesday night salons of the widowed Comtesse Rosa de FitzJames at 142 rue de Grenelle, which is now the Swiss Embassy. In fact, it was at Rosa’s salon that Edith first met the roguish Morton Fullerton.

You can tell that Jenny Fields had fun playing with the attraction between Edith and Morton in Age of Desire. At their first meeting, Morton told Edith that he’d read and enjoyed The House of Mirth, and impressed Edith by asking about Lily Bart. Nice ice breaker for a writer, right? When they discovered they were mutual friends of Henry James, Edith was definitely intrigued. She couldn’t wait to see Morton again.

But Edith would have to wait. Discretion prevailed. When Henry James came for an extended visit at Edith’s, Morton dropped by as often as he could. Edith and Morton finally had a private get-to-know-you walk through Edith’s posh Left Bank neighborhood, “the sun . . . splash[ing] itself all along the high-walled hotel particuliers of the rue de Varenne.”

In the pages of Age of Desire, Edith and Morton strolled down to the nearby lawns of Les Invalides. When they sat down in a nearby garden, things really started to buzz:

In the garden, they locate a bench and sit side by side. She can sense his body heat, and takes in his odor of driftwood and lavender. Edith feels something she hasn’t felt in a long time and cannot name. . . .

[Morton says,] “See that honeybee?” On the hedge behind them, a honeybee as far as a blackberry is trying to wedge himself greedily into the narrow trumpet of a pink flower. Fullerton turns his gaze to her and says, “That’s how drawn I am to you.”

Really, Morton, you little devil. No more Age of Innocence for Edith.

Square d’Ajaccio near Les Invalides in Paris. I could easily picture Edith and Morton on one of those benches. It was a pretty romantic park in real life. One amorous couple kissed shamelessly on a bench while another were entangled in the grass. Ah, Paris!

Unfortunately, Edith’s newfound passion would have to wait some more. The Whartons returned each spring to their palatial home (The Mount) in Lenox, Massachusetts, and would not return to Paris until December, 1907.

Edith and Morton’s relationship finally escalated the next season in Paris. They snuck off on long walks through Montmartre, the Tuileries, and Luxembourg Gardens. They met at the Louvre, took daring trips in her car. Their love become ostentatious; people took notice. But Edith didn’t care. How can a woman say no to those little green boxes of macarons framboise from La Durée?

“Instead of flowers, [Morton] proffers a pale green box of gleaming pastel macaroons from Laduré, the pastry shop on Rue Royale.”

“It’s just like my brother to choose to live in Paris but reside on a street called American Place,” she says.

“Ah yes [says Morton]. Sophisticated Mrs. Wharton wouldn’t be caught dead here . . . and yet here you are!”

A lovely old residence on Place Etat-Unis, a beautiful square in the 16th arrondissement where Edith’s brother Harry Jones lived. Yes, it’s true, a lot of Americans lived there and still do. In this scene in the novel, Fields does a great job of capturing Edith’s Left Bank snobbery.

Edith may not have cared for her brother’s neighborhood, but she adored staying at the Hotel Crillon on La Place de la Concorde. She often checked herself into the Crillon in before or after the Vanderbilt place was available. In April 1909, Edith tucked herself into the Crillon and worked on her next novel, Custom of the Country. Edith’s affair with Morton was sputtering at the time, and according to Age of Desire, she refused to have a secret rendezvous with him at the Crillon, no matter how strong his hints.

The folks at the Crillon’s boutique were good sports and let me take this photo of a Hotel Crillon bathrobe. I was trying to picture Edith in a robe and slippers, scribbling away about Undine Spragg’s time in Paris, but that got a little weird.

Even if you can’t swing a month at the Crillon like Edith, you can still enjoy a nice Sancerre on the terrace.

By 1909, Edith has decided to find a place of her own in Paris. Both her marriage and her relationship with Morton are troubled, but she can at least find happiness abroad.

Edith lands on the perfect apartment at last. And to think it’s just across the street from the Vanderbilts’ on the Rue de Varenne. But bigger, and newer, with its own guest suite and servants’ quarters and steam heat! Unheard of in Paris. And what makes it so extraordinary is that the rooms are luxuriously spacious and overlook a small but elegant garden. A garden! It’s all she could want in space and light. Precisely in the part of the Faubourg she loves.

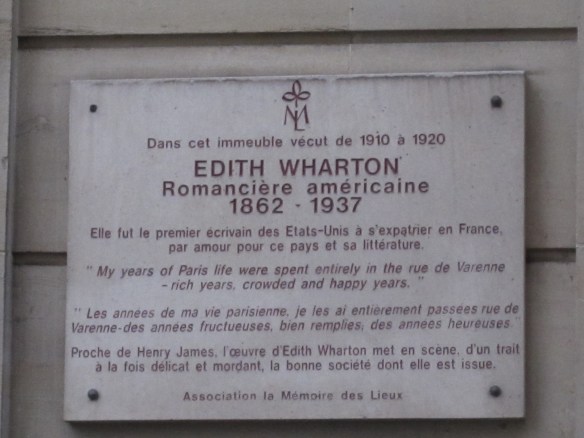

The plaque at 53 rue de Varenne commemorating Edith Wharton’s years here (1910-1920), her love for France and her friendship with Henry James.

The carriage door was open, so I was able to walk inside toward the courtyard and glimpse a peek of the lovely tiled lobby of Edith Wharton’s former townhouse at 53 rue de Varenne.

The view of the back of Edith Wharton’s apartment at 53 rue de Varenne, which overlooked beautiful private gardens. Look again at the cover of Age of Desire. Looks like Edith could be standing right there, doesn’t it?

Fouquet’s on Champs Elysée. You can have a perfectly pleasant (although pretty expensive) dinner there, unlike the miserable dinner Edith and Morton had toward the end of the book!

If you find yourself in Paris and would like to have your own Edith Wharton Day, just follow along on my Google Map. I would recommend starting at the Rue de Bac Métro stop, walking down the rue de Varenne, and then heading over to Les Invalides. From that point you can walk across the Seine or hop back on the Métro to get to the Crillon, La Durée and Fouquet’s. After some macaroons from La Durée, a glass of wine at the Crillon and dinner at Fouquet’s, you’ll definitely feel spoiled, and perhaps, a little like Edith.

Age of Desire is an entertaining treat for Edith Wharton fans, but is also a good read for those who haven’t yet read her work. Be prepared, though, because after you read Age of Desire, you could end up spending the next month holed up in a chair, getting nothing else done, reading or re-reading all of Edith Wharton’s marvelous novels and stories. To those purists who object when their favorite literary icons are injected with thoughts and actions from another author’s imagination, I say just give it a try. Play along.

Jennie Fields does a fabulous job following Edith and Morton through Paris and beyond. In the course of her research, Jennie visited Herblay, Senslis and Montmorency, some of the towns outside Paris to which Edith and Morton snuck off to for their trysts. Field’s research pays off. I thought it was beautifully imagined and very well researched. It’s definitely a recommended read.

Related articles

- Edith Wharton and Friends in Vogue (vol1brooklyn.com)

- ‘Age Of Desire’: How Wharton Lost Her ‘Innocence’ (wnyc.org)

- Vogue Dressed Up Jeffrey Eugenides and Junot Diaz for an Edith Wharton Spread [Mag Hag] (jezebel.com)

- Is Edith Wharton the New Jane Austen? (blogher.com)

Dreams of Giverny

Time flies. The 25th Anniversary Edition of Linnea in Monet’s Garden is about to be released this fall by Sourcebooks. It doesn’t seem that long ago that my daughter received her own treasured copy from her grandmother. We read that book over and over, dreaming of the day when we could travel to Giverny together to stand on that bright green bridge over the lily pond.

We finally did.

My daughter and I are standing on Monet’s bridge, after dreaming about it for nearly 20 years. Inspired by one of our favorite children’s books, Linnea in Monet’s Garden.

It was everything we dreamed of. The pink house, the yellow kitchen, the pebbled garden walk. Except for the crowds. I was stunned at the number of visitors in Giverny as compared to my first visit to in the late 80’s. You have to snap your photos fast, before yet another group of cruise boat tourists wanders into your viewfinder. We’re still glad we went – it’s a treasure of a place.

Once my mission had been accomplished with my own daughter, I thought it was time to get a new generation of girls in my family dreaming about Giverny. I had planned on buying a copy of Linnea in Monet’s Garden for a niece’s birthday, but the current edition was out of print, and I didn’t want to wait until October for Sourcebooks’ anniversary edition. Luckily, I stumbled upon another lovely children’s book called Charlotte in Giverny (Chronicle Books).

Charlotte in Giverny is the fictional journal and scrapbook of a young girl whose family travels to the Giverny art colony in 1892. The book contains whimsical watercolor illustrations, historical photographs and museum reproductions of famous Impressionist paintings created in Giverny.

It’s a terrific little book and it’s not just for kids. It’s got a lot of art history that’s quick and easy to browse through. Charlotte is a bright and observant little journalist, and brings a youthful sense of wonder to the subject. Charlotte in Giverny offers much more than the story of Claude Monet. You get to hear about the whole colony, and about other American artists such as Lilla Cabot Perry, Thomas Robinson and Mary and Frederick MacMonnies.

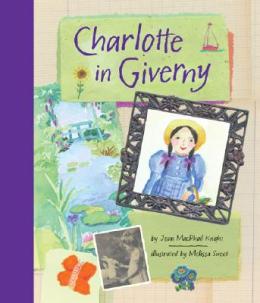

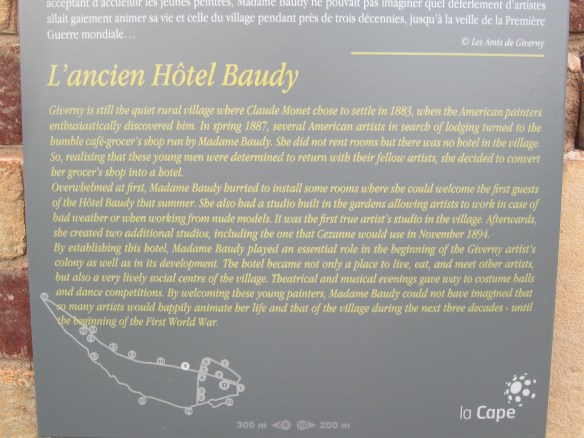

Charlotte and her family check into Hotel Baudy upon their arrival in Giverny, just like so many of the visiting American artists in the late 19th century. Charlotte enjoys the boisterous life at the hotel, where the artists often pay their hotel bills by leaving a painting behind. If you visit Giverny today, you can enjoy lunch inside the old Hotel Baudy, or on the terrace where the old tennis courts might have once stood.

Degas, is that you? In Charlotte in Giverny, Charlotte meets the American painter Lilla Cabot Perry and her young daughter Edith. The Perrys had a little dog named “Degas” who looks a lot like this petit chien!

The interior of the Hotel Baudy, where you can imagine all of the fun bohemian evenings singing songs near the fire. The walls are full of Impressionist reproductions that might have been left behind by starving artists unable to pay their bills.

You can enjoy lunch on the terrace of the Hotel Baudy, which might be the site of Hotel Baudy’s old tennis court. Karl Anderson’s painting called “Tennis Court at the Hotel Baudy” (1910) depicts a tennis scene on a court right outside the hotel. To me, it looks as though it could have been right here. See for yourself on the Terra Museum website.

Charlotte gets to know the other American artists who called Giverny home, including Lilla Cabot Perry who rented Le Hameau in the summertime, and Frederick and Mary Fairchild MacMonnies (later known as Mary Fairchild Low) who lived in Le Moutier, a former monastery which was jokingly referred to as “MacMonastery.”

Le Moutier – from a 1960s era postcard. The former home of American artist power couple Frederick and Mary Fairchild MacMonnies.

Today, Le Moutier is privately owned and protected by high walls, just like it was back in the “MacMonastery” days.

Despite the crowds, you can’t beat a day trip to Giverny in Charlotte or Linnea’s footsteps. It’s a lovely village full of art, history and pastoral beauty. You don’t need to have a daughter to enjoy the trip or these books. You just need to have the heart of an artist.

Recommended visit: Take the train to nearby Vernon, rent a car, or take a bus tour from Paris that allows you an entire day to wander through the streets of Giverny. Don’t rush back!

Additional recommended reading: Charlotte in Paris

Happy 100th Birthday “Dearie” – A Julia Child Tour of Paris

August 15, 2012 marks the 100th anniversary of Julia Child’s birth, and with perfect timing, Bob Spitz has authored an affectionate and definitive biography called Dearie (Knopf, August 8, 2012). I just downloaded my own Google ebook edition from my favorite independent bookstore.

If you admire this quirky powerhouse of a woman, you’ll love reading about her upbringing in California and her work at a spy agency during World War II, as well as her life in France and beyond.

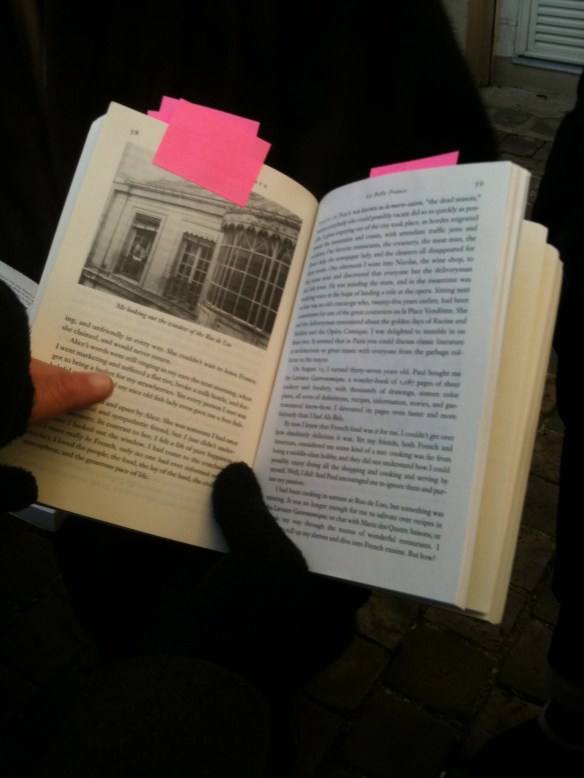

For me, Julia’s 100th birthday is the perfect time to reflect on my good fortune in being able to walk in her footsteps in Paris. On a freezing cold day last January, I joined the American Women’s Group in Paris on a private Julia Child Tour.

We were already shivering and stomping our cold feet when we met at the site of Julia Child’s Paris apartment at 81 rue de L’Université (or as Julia and Paul cheerfully called it, “Rue de Loo.”) We had private arrangements to meet the landlord in the courtyard of the building. We didn’t know what to expect, and were excited just to be there, despite the historically low temperatures.

It turned out that the landlady was an utterly charming French woman. She came out into the courtyard dressed in a fashionable fur coat, with her gray hair neatly brushed back into a black velvet headband. She spoke only French, but our tour guide was able to translate what we were unable to understand on our own.

Madame was happy to share her deceased husband’s stories about growing up as a neighbor of Julia and Paul Child. He was a young boy at the time, and would often ride his bicycle in the courtyard. Julia was never too busy to stop and visit with him, and obviously enjoyed the company of children. Julia’s French neighbors adored her. According to Madame, they remembered her as tall, outgoing and extremely friendly.

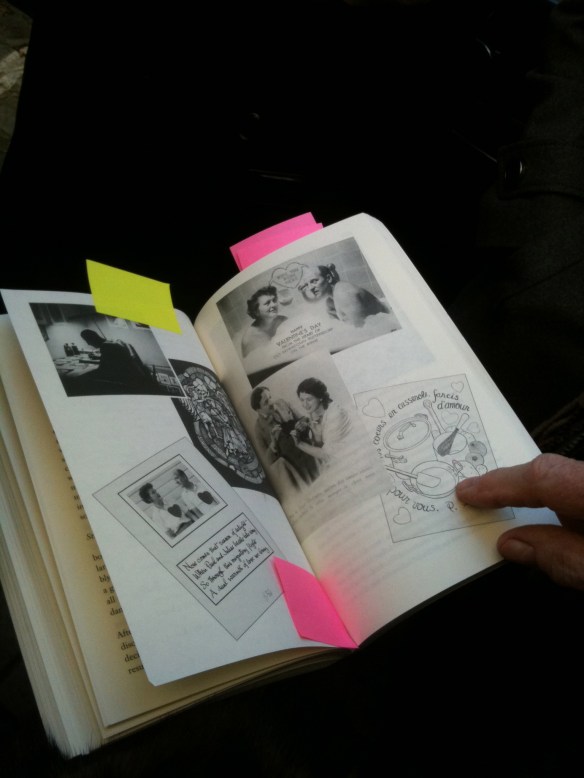

Madame told us that her husband’s family received Christmas cards from Julia and Paul for many years, even after they had left Paris. Madame apologized: she had searched for them among her old scrapbooks and souvenirs before our visit but couldn’t find them. She paged through her copy of My Life in France and pointed to the famous Christmas card with Julia and Paul in the bathtub, and said proudly: “I have this one somewhere!”

We were thrilled when Madame invited us up to her apartment, and not just because we were eager to escape the cold. We got a glimpse at an apartment similar to the one Julia and Paul lived in. While the living room and dining room were lovely, with classic wood parquet floors, gloriously tall windows and exquisite decorative wood moulding, the kitchen was excrutiatingly small. We got to peek up the stairs toward the third floor, and I couldn’t help but think of one of my favorite scenes in the Julie and Julia movie when Paul used to come home for lunch and a “nap” in the middle of the day.

In our best intermediate French (“Merci beaucoup Madame! Enchanté!”) we thanked Madame for her hospitality. We then hopped on a bus and continued our tour in the Les Halles neighborhood, where Julia used to shop for ingredients and cooking supplies. We finally warmed up with traditional French Onion Soup and a little white wine at Au Pied du Couchon, just like Julia did so many years ago. What fun.

Happy Birthday, Julia! And Madame, thanks for the memories.

Another ordinary looking apartment building in the 7th arrondissement in Paris. There is no plaque, so most passerby would never realize that this was once the home of Julia and Paul Child.

Julia and Paul’s apartment was on the third floor. (In France, they don’t count the ground floor as the first floor – get s a bit confusing sometimes!) A photo of these very windows appears in My Life in Paris.

Madame brought her own stickered-up copy of My Life in France in order to compare the photos to the scene in the courtyard. She pointed up at the windows to show us where Julia and Paul had lived.

Julia and Child’s apartment was on the third floor. Julia began cooking in the original kitchen, which was extremely small even by Paris standards. They later converted the small attic apartment above into a separate kitchen. Paul took the photo that appears in My Life in France (pictured above) from one of these third floor windows, aimed across the courtyard and toward the decorative windows in the other wing of the apartment.

Madame is pointing out the photos of Julia and Paul’s Christmas cards that her husband’s family used to receive. She apologized because she hadn’t been able to find the scrapbook where they had been stored!

E. Dehillerin in Les Halles, a classic French cooking supply store where Julia used to shop. Still a very friendly place to browse.

Our crazy French waiter at Au Pied du Couchon, who led us in a traditional French chanson, complete with a pig nose!

Additional reading:

Mary Cassatt’s Greater Journey

In The Greater Journey (Simon & Schuster), McCullough turns his storytelling gifts to the many Americans who came to Paris between 1830 and 1900. As McCullough says, “Not all pioneers went west.”

Among these pioneers were young men and women who would come to study art in Paris, including George P. Healy, John Singer Sargent, Mary Cassatt and Augustus St. Gaudens.

First Mary Cassatt. Because I love her story.

Cassatt was from a proper and prosperous Pennsylvania family who could afford to travel through Europe. After studying art in Philadelphia, she told her father that she wanted to study art abroad. He tried to discourage her (“I’d almost rather see you dead than become an artist!”) but he gave in like dads are known to do.

Cassatt would travel and study through Europe in the 1860s and early 70s, from Italy to Spain to France, studying under such French masters as Jean-Léon Gérome, Charles Chaplin and Thomas Couture. She would succeed in having her first painting accepted to the Paris Salon in 1868. According to McCullough:

For Mary her time in France had determined she would be a professional, not merely “a woman who paints,” as was the expression. Commenting in a letter on just such an acquaintance, she was scathing: “She is only an amateur and you must know we professionals despise amateurs. . . .”

Cassatt would decide to live in Paris in 1874, and thereafter make France her home for the rest of her life. Mary and her older sister Lydia moved into a small apartment on rue de Laval (now Victor Massé). It was a street known for artist’s homes and studios. Cassatt would become close friends with Degas (who lived and worked on rue Victor Massé for many years), discovering his pastels in a gallery window on nearby boulevard Haussman.

In 1878, Cassatt’s parents decided to come live in Paris, and together they moved to a larger apartment at 13 avenue Trudaine, in the respectable streets at the foot of Montmartre. There, Cassatt could be close enough to walk to her and her friends’ art studios, but yet far enough away to be proper. They had a beautiful view of Sacré Couer from their fifth floor apartment.

13 avenue Trudaine, home of Mary Cassatt and family from 1878-1884. (Funny anecdote: the day I tracked down this address, I was excited to notice a film crew on the street in front of the former Cassatt home, and I thought, “How exciting! They’re filming a movie about Cassatt!” No, they were filming next door. Nothing to do with Cassatt. I obviously live in a bubble of art history and assume the rest of the world does too.)

At about this same time, Degas invited Cassatt to join the Impressionists, the first and only American in the group, and only the second woman (besides Berthe Morisot). Cassatt would join in their Fourth Impressionist Exhibit in 1879. It was a good fit for Cassatt, who despite her thoroughly conventional background, had an independent and blunt personality. She was not well suited for the politics and brown-nosing required to fit in the Paris art establishment:

Finally I could work with absolute independence without concern for the eventual opinion of the jury. . . . I detested conventional art and I began to live.

Once her parents moved to Paris, Cassatt turned her focus toward domestic family portraits of her mother, sister, nieces and nephews. Her portraits would not be highly flattering society portraits, but rather, beautiful studies in composition and mood. Her women would be introspective and intellectual, utterly without pretense, often concentrating on a task, a newspaper or a book. In Cassatt’s 1878 portrait of her mother, Cassatt builds an intriguingly complex composition through the use of a mirror on the left half of the canvas that emphasizes the act of reading.

Mary Cassatt, Reading Le Figaro (Portrait of Cassatt’s Mother) 1878. Displayed in Fourth Impressionist Exhibit in 1879.

Cassatt may suffer from a modern feminist bias against highly domestic scenes with women and children, as if Cassatt agreed that this was the only proper sphere for women. In fact, Cassatt was a highly ambitious artist who never married and who was responsible for earning her own living. Cassatt’s tough-love-count-every-penny father demanded that she pay for her own studios and art supplies from the sale of her work. She did.

Unlike the male Impressionists, Cassatt could not properly hang out at the cafés and nightclubs of Montmartre. However, she did enjoy going to the opera about four times a week in the company of close friends and family. Here she would be able to sketch out a fascinating series of paintings.

While the painting of Cassatt’s sister Lydia in the evening dress might be more traditionally pretty, it is her pose in a black dress at a matinée that is more interesting, and seems to have the more to say. In fact, if you have a couple extra minutes, you should really listen to this “Smart Art History” video about Cassat, the Paris Opera and the painting below.

By the late 1880s, Cassatt was finding her own success and beginning to sell many of her paintings. She and her family would find a larger apartment in an even nicer part of Paris at 10 avenue Marignan near the Champs-Élysées by 1887. Cassatt would keep this apartment for the rest of her life, although she and her family would rent numerous summer homes in the suburbs of Paris.

The plaque at 10 rue de Marignon in the 8th arrondissment of Paris: “American Impressionist Painter – Friend and Colleague of Edgar Degas.” (Commentary: Why do the plaques commemorating a woman have to mention their relation to a man? I noticed the same thing on Edith Wharton’s plaque on rue Varenne in Paris, which mentioned that Wharton was a friend of Henry James.)

Mary Cassatt lived the rest of her life in Paris and its suburbs, dying in 1926 at her country chateau in Beaufresne, one of the last of her generation who had come to Paris in the 1860s. She was a significant part of America’s “Greater Journey.” And because she was a woman, her story is even more remarkable. Like Ginger Rogers, she had to do it “backwards and in heels.”

The Greater Journey by David McCullough: Highly recommended. Also recommended, Lydia Cassatt Reading the Morning Paper by Harriet Scott Chessman.

Some V-E Day Reading Recommendations

May 8th is a National Holiday in France in honor of Victory in Europe Day, the day the Allies accepted the unconditional surrender of Nazi Germany in World War II. It brings to mind all of the good literature, both fiction and nonfiction, that has been written about this time period in Paris. Just a few recommendations to share with you.

Americans In Paris: Life and Death Under Nazi Occupation by Charles Glass is an excellent and highly readable account of the Americans who stayed behind after France declared war on Germany, and even after the United States entered the war. Just like the French who stayed in Paris, many of the Americans who stayed lived in the grey area between resistance, collaboration and survival.

Except of course, Sylvia Beach, the owner of the original Shakespeare & Co. She stood her ground and refused to sell the last copy of Finnegan’s Wake to a German soldier, insisting on saving it for an English-speaking customer. Beach knew she had infuriated the German officer, so within hours, she packed up all of the books in the bookshop and moved them a few doors down to her apartment on rue Odéon. She never re-opened her shop again.

Another excellent nonfiction account of the Occupation era is And The Show Went On: Cultural Life in Nazi-Occupied Paris by Alan Riding. A thoroughly researched book, this one focuses on the ways that the Parisian culture – from the opera and the nightclubs – continued to thrive under the Nazis, although with considerable censorship and control. Sylvia Beach again merits attention, as does the Rose Valland, the surprising heroine of the Jeu de Paume who kept meticulous records of the artwork plundered by Hitler, Goring and their associates, so that it could be tracked down after the war. Again, there are the complicated issues of collaboration and resistance, which Americans seem to find so difficult to comprehend. Fascinating.

I am also recommending a book that it completely new to me; in fact, I have just ordered it thanks to the folks at Paris Walks, who read a powerful excerpt during my recent Left Bank During The Occupation tour. It is called The Journal of Helene Berr, and it sounds like Diary of Anne Frank, except written by a mature, college-educated Parisian. Like Anne Frank, she was Jewish, she was deported and she was killed just before the war was over, but her diary has survived. Although this book was originally published in French, it is also available in English.

Finally, I must mention Suite Française by Irene Nemirovsky. It has received many well-deserved accolades, and was very well received by many book clubs when it was released, so it should be no surprise. But if you haven’t read it, I urge you to read it now. This is powerful fiction. Much of it is based on Nemirovsky’s own experiences as a Jewish woman who escaped Paris with her family to live out most of the war in Issy-l’Évêque, a small town in Burgundy. Like Helene Berr, Nemirovsky was eventually deported and killed, but her daughters kept her manuscripts hidden in a suitcase. I really, really loved this book.

In previous posts I have written about two other World War II era works of fiction set in Paris: Sarah’s Key by Tatiana de Rosnay, and Pictures at an Exhibition by Sara Hoghtelling. Check out my earlier posts for a photo tour of some of the scenes from these books.

I would love to hear any World War II era books you might recommend, especially those set in France.

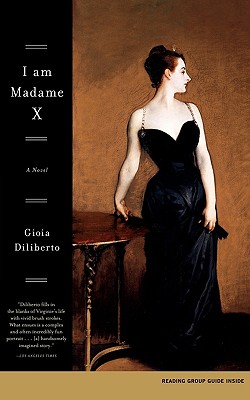

John Singer Sargent and Madame X in Paris

I first read Gioia Diliberto’s I Am Madame X back in 2004. I might have even picked it as a book club read. It’s a fabulous Belle Epoque novel about the life and times of the celebrated 19th century American portrait artist John Singer Sargent and his most infamous model, American beauty Virginie Gautreau.

I read it again recently, because John Singer Sargent’s name keeps popping up on my travels through Paris art history. This book is even better the second time around, especially now that I know my way around Paris and I can really appreciate what it meant to be a Left Bank artist versus a Right Bank Artist.

John Singer Sargent had the best of both worlds.

He was the son of a wealthy, cosmopolitan American family that had lived abroad for decades by the time they arrived in Paris in 1874. They settled into a posh Right Bank apartment near the Champs-Élysées, which has since become a commercial building at 52 rue La Boétie. Sargent’s father took him to meet the young teaching master Carolus-Duran, who ran a popular Left Bank painting atelier in the heart of Montparnasse.

Sargent was only 18 years old, but he was already bursting with talent. He quickly earned the admiration of his fellow students and within a year was accepted at the rigorous L’Ecole des Beaux Arts. In 1875, Sargent moved out of the family’s home and into a fifth-floor studio apartment at 73 rue Notre-Dame-des-Champs with fellow art student James Carroll Beckwith.

The young American artists had found a promising location. The studios at 73 rue Notre-Dame-des-Champs had also housed the famous French painter Jean-Paul Laurens, while 75 was the mansion-atelier of Adolphe William Bourguereau. By the 1860s, this small, winding road had already been nicknamed “the royal road of painting.” Even today, the address looks inspiring. It still has an impressive entrance and an inviting green courtyard.

Sargent, Beckwith and their pals led a young bohemian life in the Left Bank. They worked hard but still had time for wild evenings, moving the easels aside for dancing and drinking right in the studio. Sargent was known for entertaining his guests on a rented piano. On Sunday nights, they would clean themselves up for a proper dinner party at Sargent’s family’s home with “educated and agreeable” conversation.

Courtyard of 73-75 rue Notre-Dame-des-Petit-Champs. Back in the 1870s, the gardens probably went all the way through to Luxembourg Gardens

In 1879, Sargent painted the portrait of his art teacher Carolus-Duran, and it absolutely launched his career. It was bold, theatrical, and presented a stunning likeness in both spirit and physicality. Sargent was only 23 years old and already one of the best portrait artists in France.

In Diliberto’s novel, Sargent meets the future Madame X at a Montparnasse restaurant. In reality, they may have met when Gautreau attended an informal party at Sargent’s studio on rue de Notre-Dame-des-Champs in 1881. Sargent was celebrating the completion of his portrait of Dr. Pozzi, one of Gautreau’s many reputed lovers. According to Diliberto, Gautreau was shocked by Sargent’s portrayal of Dr. Pozzi, a charismatic ladies man (and gynecologist) who had ungraciously tossed her aside before her marriage to Pierre Gautreau:

On an easel near the French doors stood Sargent’s painting of Dr. Pozzi. It looked like a portrait of the devil. Virtually the entire canvas was red – the sumptuous curtains in the background, the carpeted floor. The doctor himself was dressed in red slippers and the red wool dressing gown that I had seen him wear dozens of times. His pose was hypertheatrical; his face was caught in an intense observance of an object outside the canvas, and his elongated fingers tugged nervously at his collar and the drawstring of his robe. His fingers were as sharp as pincers and seemed spotted with blood. Had Pozzi just performed a gynecological operation? Deflowered a virgin?

I just love how Diliberto gave Gautreau such a blunt and penetrating voice. She is clearly no innocent about men, or for that matter, about Sargent’s ability to portray a model’s true character.

Sargent was determined to get the chance to paint Gautreau’s portrait. He obviously understood the PR value of painting the “professional beauty” who was the focus of such much attention and gossip in the affluent social circles of Paris. Gautreau thought about giving her business to other more traditional French portrait artists, but she may have felt a special connection to Sargent. They were both up-and-coming Americans with something to prove to the French.

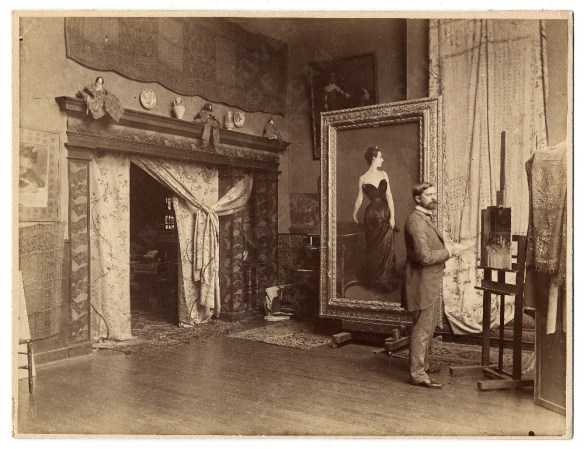

In the meantime, steady commissions enabled Sargent to buy a large, new home and studio on the Right Bank, closer to all of his wealthy patrons. In the winter of 1883-84, Sargent moved to 41 boulevard Berthier, on the shaded side of a wide street whose light made it a popular location for art studios. It wasn’t far from the new mansions near Parc Monceau, and in fact just a few blocks from Madame Gautreau who lived at 80 rue Jouffroy d’Abbans.

In The Greater Journey, David McCullough describes Sargent’s new Right Bank studio:

. . . a workplace elegantly furnished with comfortably upholstered chairs, Persian rugs, and drapery befitting his new professional standing, and with an upright piano against one wall, . . .

No longer would Sargent’s patrons have to track through the mud and past the questionable bohemians on rue Notre-Dame-des-Champs.

41 boulevard Berthier has been replaced by a newer building, but this one next door is a good example of the types of buildings that once dominated the street, with large windows and skylights on the top floors. It was on this street that Virginie Gautreau would have gone to pose for her portrait.

Parc Monceau in the 17th, the center of the fashionable new Plaine Monceau area of the 1870s-80s. Monet painted this park several times.

By 1883, Gautreau finally agreed to pose for Sargent. He talked her into wearing a black dress that would highlight her unusual color, which included rouged ears, white pastey skin (thanks to lavender skin cream) and brightly hennaed hair. At the end of the day, Sargent may have painted her color a little too well. He captured her true character, just like he had with Dr. Pozzi. Her pose was so confident it seemed haughty.

But the strap was the last straw. The painting we know now, as it appears at the Metropolitan Museum in New York, was retouched. The original painting looked like this – a little risqué, no doubt, but more balanced and much more interesting.

Nevertheless, it was a disaster at the 1884 salon. “Quelle horreur!” said polite Paris society. One critic said the flesh “more resembles the flesh of a dead than a living body.”

Sargent soon left for the summer in London while Gautreau disappeared to Brittany, far from the judgment of Paris. Sargent would keep his Paris studio on boulevard Berthier for two more years, where he proudly displayed Madame X.

Although Sargent may have misjudged the limits of Right Bank tolerance and underestimated their hypocrisy (after all, many of the traditional paintings in the Salon were nudes, and they’re complaining about a little strap?), he would later say that Madame X was “the best thing I have done.”

John Singer Sargent in his boulevard Berthier studio with a retouched Madame X. The strap is repainted.

If your read I am Madame X you will find out much more about Virginie Gautreau: her New Oreans background, her family’s escape to Paris during the Civil War, her early years in a Paris convent school. It’s a well-told story in the voice of a fascinating woman.

I am Madame X by Gioia Diliberto: HIghly recommended.

Berthe Morisot’s Interior

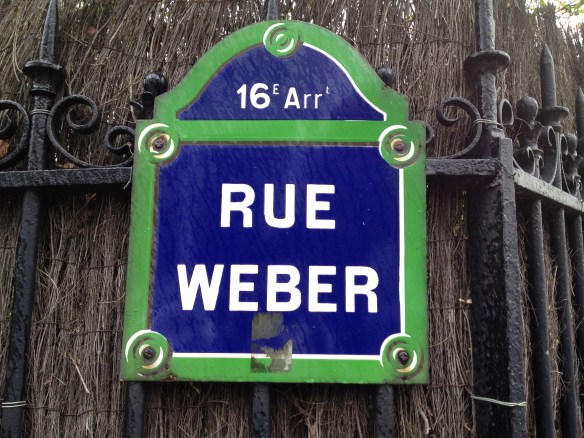

In this 1893 painting, Berthe Morisot pictures her teenage daughter Julie in the interior of their apartment at 10 rue Weber, where they moved after the 1892 death of Morisot’s husband Eugene Manet. I think it tells us a story about the interior of Morisot’s own life.

One of the first things I notice is the portrait of Morisot hanging on the wall to the left of the fireplace. Her brother-in-law Édouard Manet painted it in 1873, when Morisot was thirty-two years old and had just started showing with the Impressionists. Manet gave it to Morisot as a gift. I am always struck by the pose and the gaze that Manet captured. Pretty sensuous. Yet one year later, Morisot would marry Édouard’s brother. Twenty years later, after both Édouard and Eugene have died, Morisot paints a picture with this portrait in the background.

There are a few other interesting details in the painting of Julie and a Violin. According to Julie Morisot, who is quoted in the Exhibition Catalog for the Berthe Morisot Exhibit at the Musée Marmottan, the painting to the right of the fireplace – which is cut off and barely even depicted – is a painting of her father by Degas. In the center of the painting behind Julie, there is a large Chinese bowl, a treasured gift from Édouard Manet. Notice how close it is to the fireplace, how bright and prominent it is in the center of the room next to Julie. Finally, consider the empty yellow chair facing Morisot’s own portrait. It has been placed there on purpose – why else would it be facing the wall and not Julie?

I think we know. The two most treasured people in Morisot’s life were her daughter and Édouard – not Eugene – Manet. But of course, I’m just speculating, drawing wild conclusions from a pretty painting. And yet, I know that everything in the background of a painting is carefully selected and placed there for a reason, just like the details in a book. I think this painting hints at a really good story.

If you go to rue Weber today, you can find Morisot’s lovely apartment still standing. There is no historical marker, and few of the neighbors I spoke to even know it was once Morisot’s home. It is one of the loveliest streets in Paris, in a quiet corner of the 16th arrondissement that ends at the Bois de Boulogne. Despite their loss and grief, Morisot and her daughter must have had some simple pleasures their last two years there together, with frequent walks and sketching opportunities in the nearby park.

Morisot would catch pneumonia in 1895 and die at the age of 52. Julie would come under the guardianship of a Manet family friend, the poet Stéphane Mallarmé, until his death in 1899.

Morisot’s secret interior would live on in her paintings. You can see many of them for yourself at the special Berthe Morisot Exhibit at the Musée Marmottan until July 1, 2012.

You must be logged in to post a comment.