In The Greater Journey (Simon & Schuster), McCullough turns his storytelling gifts to the many Americans who came to Paris between 1830 and 1900. As McCullough says, “Not all pioneers went west.”

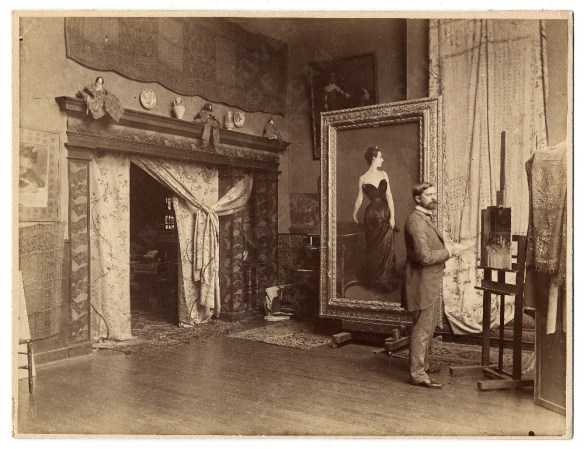

Among these pioneers were young men and women who would come to study art in Paris, including George P. Healy, John Singer Sargent, Mary Cassatt and Augustus St. Gaudens.

First Mary Cassatt. Because I love her story.

Cassatt was from a proper and prosperous Pennsylvania family who could afford to travel through Europe. After studying art in Philadelphia, she told her father that she wanted to study art abroad. He tried to discourage her (“I’d almost rather see you dead than become an artist!”) but he gave in like dads are known to do.

Cassatt would travel and study through Europe in the 1860s and early 70s, from Italy to Spain to France, studying under such French masters as Jean-Léon Gérome, Charles Chaplin and Thomas Couture. She would succeed in having her first painting accepted to the Paris Salon in 1868. According to McCullough:

For Mary her time in France had determined she would be a professional, not merely “a woman who paints,” as was the expression. Commenting in a letter on just such an acquaintance, she was scathing: “She is only an amateur and you must know we professionals despise amateurs. . . .”

Cassatt would decide to live in Paris in 1874, and thereafter make France her home for the rest of her life. Mary and her older sister Lydia moved into a small apartment on rue de Laval (now Victor Massé). It was a street known for artist’s homes and studios. Cassatt would become close friends with Degas (who lived and worked on rue Victor Massé for many years), discovering his pastels in a gallery window on nearby boulevard Haussman.

In 1878, Cassatt’s parents decided to come live in Paris, and together they moved to a larger apartment at 13 avenue Trudaine, in the respectable streets at the foot of Montmartre. There, Cassatt could be close enough to walk to her and her friends’ art studios, but yet far enough away to be proper. They had a beautiful view of Sacré Couer from their fifth floor apartment.

13 avenue Trudaine, home of Mary Cassatt and family from 1878-1884. (Funny anecdote: the day I tracked down this address, I was excited to notice a film crew on the street in front of the former Cassatt home, and I thought, “How exciting! They’re filming a movie about Cassatt!” No, they were filming next door. Nothing to do with Cassatt. I obviously live in a bubble of art history and assume the rest of the world does too.)

At about this same time, Degas invited Cassatt to join the Impressionists, the first and only American in the group, and only the second woman (besides Berthe Morisot). Cassatt would join in their Fourth Impressionist Exhibit in 1879. It was a good fit for Cassatt, who despite her thoroughly conventional background, had an independent and blunt personality. She was not well suited for the politics and brown-nosing required to fit in the Paris art establishment:

Finally I could work with absolute independence without concern for the eventual opinion of the jury. . . . I detested conventional art and I began to live.

Once her parents moved to Paris, Cassatt turned her focus toward domestic family portraits of her mother, sister, nieces and nephews. Her portraits would not be highly flattering society portraits, but rather, beautiful studies in composition and mood. Her women would be introspective and intellectual, utterly without pretense, often concentrating on a task, a newspaper or a book. In Cassatt’s 1878 portrait of her mother, Cassatt builds an intriguingly complex composition through the use of a mirror on the left half of the canvas that emphasizes the act of reading.

Mary Cassatt, Reading Le Figaro (Portrait of Cassatt’s Mother) 1878. Displayed in Fourth Impressionist Exhibit in 1879.

Cassatt may suffer from a modern feminist bias against highly domestic scenes with women and children, as if Cassatt agreed that this was the only proper sphere for women. In fact, Cassatt was a highly ambitious artist who never married and who was responsible for earning her own living. Cassatt’s tough-love-count-every-penny father demanded that she pay for her own studios and art supplies from the sale of her work. She did.

Unlike the male Impressionists, Cassatt could not properly hang out at the cafés and nightclubs of Montmartre. However, she did enjoy going to the opera about four times a week in the company of close friends and family. Here she would be able to sketch out a fascinating series of paintings.

While the painting of Cassatt’s sister Lydia in the evening dress might be more traditionally pretty, it is her pose in a black dress at a matinée that is more interesting, and seems to have the more to say. In fact, if you have a couple extra minutes, you should really listen to this “Smart Art History” video about Cassat, the Paris Opera and the painting below.

By the late 1880s, Cassatt was finding her own success and beginning to sell many of her paintings. She and her family would find a larger apartment in an even nicer part of Paris at 10 avenue Marignan near the Champs-Élysées by 1887. Cassatt would keep this apartment for the rest of her life, although she and her family would rent numerous summer homes in the suburbs of Paris.

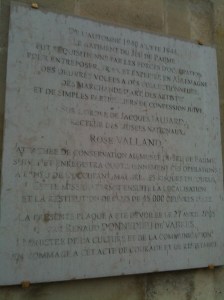

The plaque at 10 rue de Marignon in the 8th arrondissment of Paris: “American Impressionist Painter – Friend and Colleague of Edgar Degas.” (Commentary: Why do the plaques commemorating a woman have to mention their relation to a man? I noticed the same thing on Edith Wharton’s plaque on rue Varenne in Paris, which mentioned that Wharton was a friend of Henry James.)

Mary Cassatt lived the rest of her life in Paris and its suburbs, dying in 1926 at her country chateau in Beaufresne, one of the last of her generation who had come to Paris in the 1860s. She was a significant part of America’s “Greater Journey.” And because she was a woman, her story is even more remarkable. Like Ginger Rogers, she had to do it “backwards and in heels.”

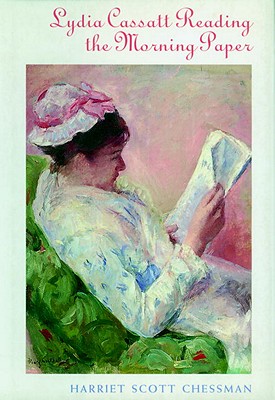

The Greater Journey by David McCullough: Highly recommended. Also recommended, Lydia Cassatt Reading the Morning Paper by Harriet Scott Chessman.

You must be logged in to post a comment.