The Other Alcott is a novel I’ve been waiting for for a long time. I’ve known about Louisa May Alcott’s younger sister – the artist, the one after whom the fictional Amy March was created – and I knew the outlines of her story. But that is like the difference between sketching a skeleton and the full, live human figure.

In Elise Hooper’s able and generous hands, May’s story is fleshed out. It thrums with life, passion and imagination, and becomes one that we can relate to. It speaks to us across the centuries, a timeless story of one woman artist that can inspire, encourage and guide 21st century women still trying to figure it out today. What else could you possibly ask from historical fiction?

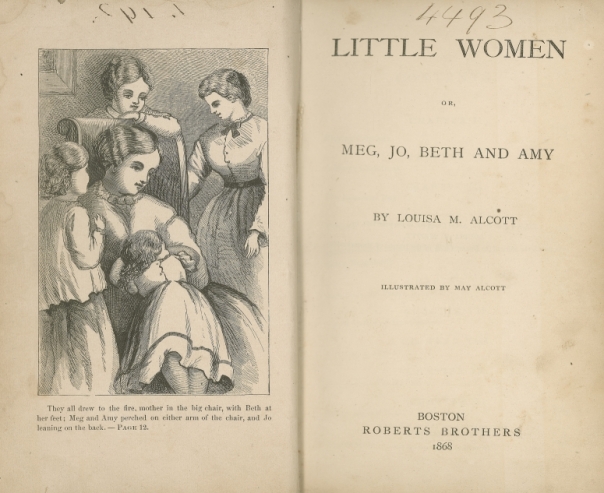

I have to admit that even I underestimated May Alcott. When I first saw the illustrations May drew for her sister Louisa’s book Little Women, I agreed with her contemporary critics. The drawings were amateurish, not lifelike enough, the product of an artist not without natural born talent, but still, with a long way to go.

I have to admit that even I underestimated May Alcott. When I first saw the illustrations May drew for her sister Louisa’s book Little Women, I agreed with her contemporary critics. The drawings were amateurish, not lifelike enough, the product of an artist not without natural born talent, but still, with a long way to go.

May Alcott illustration for Little Women (1868), source: https://sites.lib.byu.edu/literature/wp-content/uploads/sites/40/2008/09/littlewomen.jp

The Nation’s critique was brutal: “May Alcott’s poorly executed illustrations in Little Women betray her lack of anatomical knowledge and indifference to the subtle beauty of the female figure.”

The criticism stung. But yet she persisted.

May might have been hurt, but she was humble enough to understand that she needed professional instruction. (Lesson #1: Accept valid criticism.) So she figured it out.

In 1860s America, art training wasn’t an easy thing for a woman to find, especially in a small town like Concord. Victorian society was squeamish about women looking at naked bodies or studying anatomy. Nevertheless, May found a doctor in Boston who offered anatomical drawing classes to women. (Lesson #2: Ignore the prudes.) Thanks to the money from the sale of Little Women, her sister Louisa was able to afford an apartment in Boston for the two of them to share. (Lesson #3: Accept help graciously.)

May absorbed everything in Dr. Ritter’s drawing classes, but there was no drawing from life. Day after day, the women copied sketches of hands and wrists or they drew from plaster casts of skulls and human bones. May’s skills improved; her eye for the human form awakened. (Lesson #4: Start at the beginning.)

In Elise Hooper’s novel, May meets a number of established women artists who show her the way. The first is Elizabeth Jane Gardner, a Paris-trained American artist who in 1868 was one of the first women (including Mary Cassatt) who had a painting accepted in the Paris salon. They meet at a Boston art gallery (Lesson #5: Go to art galleries) where Gardner holds court and tells shocking tales about her bohemian life in Paris: dressing like a man so she could have access to live models, dragging a sick lion into her studio in order to study animal anatomy. It might have been a bit of shock and awe, but it inspired May to go to France. (Lesson #6: Listen to the stories of those who’ve come before.)

Elizabeth Jane Gardner as painted by William-Adolphe Bouguereau (her mentor, teacher and future husband) in 1879. I love how little this portrait reveals of her true spirit, except for that hint of a smile.

Inspired by Gardner’s stories, May and Louisa head off on a European adventure together in 1870. I’ve previously written on this blog about May’s first trip to France in a post titled Little Women in Dinan, France. I walked in their footsteps in the pretty historic village where May first stayed in Europe. May was frustrated that she couldn’t get to Paris for art lessons, but she spent the season exploring and sightseeing with a sketchbook in hand. (Lesson #7: Take your sketchbook.)

14 Place Saint Louis, Dinan, France, the location of Madame Coste’s pension where the Alcott sisters stayed from April to June, 1870. As Louisa May Alcott described it in a letter dated April 24, 1870: “We are living, en pension, with a nice old lady just on the walls of the town with Anne of Brittany’s round tower on the one hand, the Porte of St. Louis on the other, and a lovely promenade made in the old moat just before the door.”

May’s first trip to France was disrupted by the Franco-Prussian War of 1870, but on their detour to Italy, May finally had the chance to see nude paintings and sculptures and to draw from a live nude model. In the book, May encounters the “sniggers and chuffs” of from the men in the studio, but she ignores the sexual harassment and soldiers on, overcoming her own embarrassment in order to learn valuable skills. (Lesson #8: Nolite te bastardes carborundorum.)

May’s studies would continue back in Boston with William Morris Hunt, advancing from live drawing to oil painting, and then in London, where she copied the masters in the National Gallery and discovered the wonders of J.M.W. Turner. (Lesson #9: Study the masters.) While sketching at the gallery, May met John Ruskin, the Trustee of the National Gallery’s Turner collection, who connected her to London art dealers interested in selling her Turner copies. May finally began to earn an income from her art. (Lesson #10: Make connections.)

In 1874, May’s efforts to pursue her art in London would be interrupted by family caregiving demands. Her sister Louisa demanded that she come back to Boston to help take care of their ailing mother. But somehow May figured out a way to juggle her responsibilities at home with opportunities to study and teach art in Boston, all the while saving her money and dreaming about her chance to study in Paris. (Lesson #11: Become a skilled juggler.)

By 1877, May was making her way in the Paris art world. She got a painting accepted into the Paris salon, she met Mary Cassatt, and was seeking a way to earn a living by selling her own original paintings. In the lovely painting below, you can see how far May had come from her early days in Concord.

May Alcott Neiriker, La Nigresse, oil on canvas (1879). Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Abigail_May_Alcott_Nieriker

May’s final challenge would be to find a way to balance love and art, to make sure she continued to pursue her painting even after she fell in love and faced the responsibilities of keeping a home and starting a family. (Lesson #11: Find the nearest Planned Parenthood?)

As you can see, Elise Hooper’s book is a lovely story about May Alcott Niericker’s struggle to overcome criticism, sexism, sibling rivalry and family caregiving demands in order to pursue her dream to become a professional artist. It’s chocked full of lessons in both humility and persistence, lessons we still need today. At least I do.

The Other Alcott: Highly recommended.

For further reading:

!["The grand viaduct which, according to Murray [the Alcott's 1870 guidebook to France] is about the finest in the world, fairly took away my breath." -- May Alcott in a letter to Anna Alcott dated May 30, 1870](https://americangirlsartclubinparis.files.wordpress.com/2013/04/img_3330.jpg?w=584&h=438)

You must be logged in to post a comment.