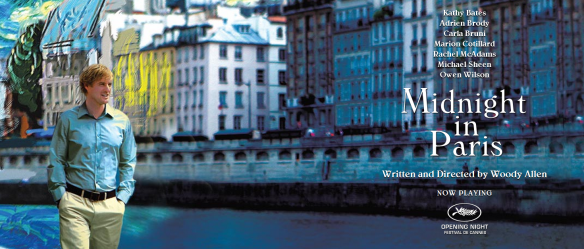

How many times have you seen Midnight in Paris? At least three? Me too. Whenever I talk to American book clubs about my literary tours of Paris, they’re always interested in Midnight in Paris sites too. So I’ve put together a list and some photos. Not exactly a tour, but a good place to start.

This list is organized according their appearance in the film, not according to a convenient walking tour. The sites are pretty widely scattered throughout Paris, so the best thing to do would be to pick one arrondissement, stumble around until you find a site or two, and then stop for a glass of wine. Repeat the next day when you’re in another arrondissement. By then you’ll have a good taste of Paris.

Opening Montage

Midnight in Paris opens with iconic Paris postcard scenes like Pont Alexandre III, Place de la Concorde, Tuilleries, Arc de Triomphe, the Seine, the Louvre, the lock bridge, Fouquets, L’Opera, Place de Trocadéro and Métro line 6 which goes over the Seine. It took me nearly a year to discover Fontaine de la Place Françoise the First, featured so beautifully in the opening montage. My husband and I stumbled into the fountain (well, not literally, although we did have a bottle or two of wine) as we were walking home from my birthday dinner one night. I can’t imagine a better way to make a discovery in Paris.

Here’s my own opening montage:

Sites In Order of Appearance in the Film

1. Opening scene – Monet’s Garden, Giverny (outside Paris)

2. Hotel scene – Le Bristol, 112 rue de Faubourg St. Honoré (8th)

3. Restaurant scene- Le Grand Vefour, 17 rue de Beaujolais, Palais Royale (1st)

4. Versailles gardens (outside Paris)

5. Jewelry store scene- Chopard, 1 Place Vendome (2nd)

6. Carla Bruni scene in garden – Hotel Biron, Musée Rodin, 79 rue Varenne (7th)

7. Rooftop winetasting scene – Hotel Le Meurice, 224 rue de Rivoli (2nd)

8. Church steps scene – St. Etienne du Mont, rue de Montagne Genevieve (5th)

9. Party with F. Scott Fitzgerald– Quai de Bourbon, Isle St. Louis, west side (1st)

10. Bricktop’s w/Josephine Baker– (imaginary location) 17 rue Malebranche (5th)

11. Hemingway’s Bar – (imaginary) Le Polidor, 41 rue Monsieur le Prince (6th)

12. Antique store – Philippe de Beauvais, 112 Boulevard De Courcelle (17th)

13. Church near antique store – Cathedral of Saint-Alexandre-Nevsky, Rue Daru (8th)

14. Back to steps at St. Etienne du Mont (5th)

15. Gertrude Stein’s – 27 rue de Fleurus (6th)

16. Flea market – Marché aux Puces de Saint-Ouen, Le Marché Paul Bert, 96-110 rue des Rosiers (18th)

17. Monet Water Lillies – Musée de l’Orangerie, Place de la Concorde (8th)

18. Bristol Hotel dining room, Le Bristol, 112 rue de Faubourg St. Honoré (8th)

19. Fairground – Musée des Arts Forains, Pavillons de Bercy, 53 avenue des Terroirs de France (12th)

20. Zelda suicide scene – along the Seine below Le Pont de la Carrousel (1st)

21. Montmartre Steps – rue du Chevalier de la Barre (18th)

22. Various Montmartre bars, back to Bristol hotel, Rodin Museum, Gertrude Stein’s, flea market

23. Bouquinistes along the Seine (5th)

24. Carla Bruni scene behind of Notre Dame – Parc Jean XXIII, Ile de la Cite (1st)

25. Taxidermy cocktail party – Maison Deyrolle, 46 rue du Bac (6th)

26. Restaurant Paul, Place Dauphine, rue Henri Robert, Isle de la Cité (1st)

27. Maxim’s – Maxim’s, 3 rue Royale (8th)

28. Moulin Rouge, 82 boulevard de Clichy (18th)

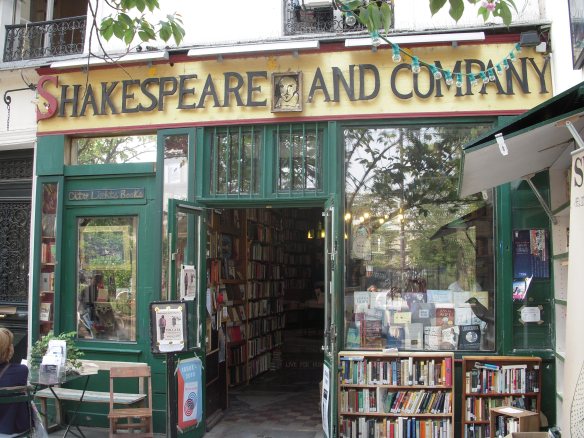

29. Shakespeare and Company, 37 rue de la Bucherie (5th)

30. Pont Alexandre III (8th)

If you’re heading to Paris, I hope you have fun creating your own individual Midnight in Paris tour. Have some wine, stumble into some fountains. . . . and enjoy.

You must be logged in to post a comment.