La Luministe by Paula Butterfield (March 15, 2019 Regal Books) is a lovely new novel about the life and art of Berthe Morisot, a French Impressionist who was able to capture the effect of light and atmosphere perhaps better than any of her contemporaries. They called her La Luministe, a nickname she most certainly earned.

La Luministe cover (don’t the easel and paint brushes make such a nice painterly touch?)

This book reads as if you are standing in front of a Berthe Morisot painting, wishing she would speak to you – and then quietly, privately, she does. And not just about her daring brush strokes or her use of quiet color, but also the secrets, the stories and the struggles hidden in each canvas. Yes, you will be fascinated to read about Morisot’s scandalous love triangle with the Manet brothers, but at its heart, this book is about a woman’s greatest passion: her art.

I absolutely loved the book and knew I’d found a kindred spirit who was as fascinated with Berthe Morisot as I was. I reached out to Paula Butterfield and she agreed to respond to a few interview questions. I hope you enjoy our chat!

- Early on in your novel, Berthe and her sister Edma create a “Bonheur Society” for themselves in honor of Rosa Bonheur. What a fun little detail. Isn’t that just what young artistic girls would do? Was this little treasure based on fact or did it come straight out of your imagination? [Note: long-term followers of this blog know I too am a big Rosa Bonheur fan. Check out my previous post about visiting her studio museum outside of Paris.]

As a women’s studies academic for almost twenty years, I saw over and over my students’ stunned reactions when they learned about previously unknown women’s contributions. I feel like when Berthe and Edma saw a Rosa Bonheur painting in person, they would have been tremendously excited and encouraged. Representation is something we consider now, and it would have been equally applicable for young 19th century would-be artists—if a woman could paint a work that earned the Legion of Honor, maybe they could, too!

Also, I wanted to illustrate the bond between Berthe and Edma. They were sisters only a year apart in age, but they were also each other’s only artistic colleagues, since girls were not permitted to attend art school or to socialize with artists. I was always forming clubs with my sister and my friends as a kid, so I guess it was only natural that I’d form a club for these two artistic sisters.

2. Which Berthe Morisot painting is your personal favorite and why? (Okay, that’s impossible, so give me your top 3.) Have you had the chance to see them in person, and if so, how did that affect your novel?

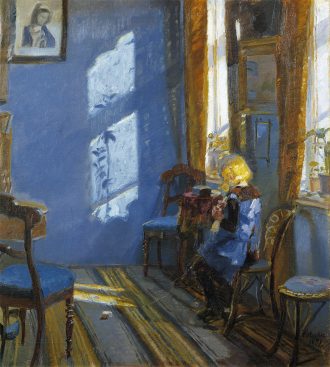

I’ve seen lots of Berthe’s paintings, in Paris, Washington D.C., Philadelphia, Chicago, San Francisco, and more places I can’t remember. And you’re right; there’s no way to choose one favorite. For my top three, I suppose I’ll choose Summer, the painting in which Berthe came closest to achieving her goal of making a figure dissolve into the atmosphere.

I’m compelled to add a painting of Berthe’s daughter, Julie, the light of her life and her favorite model. To me, this study for a painting of Berthe and Julie (tellingly, never completed) says everything about being an artist-mother. Sometimes, if you want to get anything done with your little anchor following you around, you have to integrate your child in your work!

Berthe Morisot, Self-Portrait with Julie (Study) (1887) – Private Collection

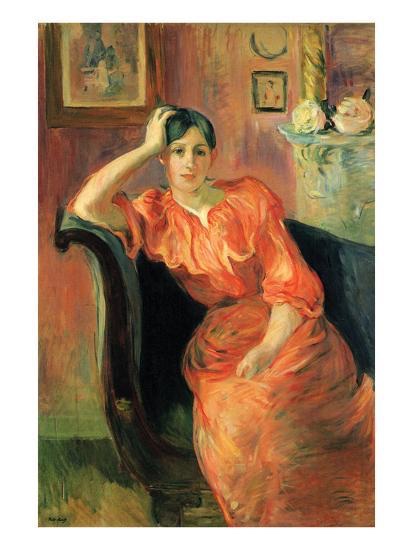

And finally, I have to include one of Berthe’s paintings from the post-Impressionist years, when she returned to Renaissance techniques. Jeanne Pontillon, a portrait of Berthe’s niece, uses rich hues and long brushstrokes.

Berthe Morisot, Portrait of Jeanne Pontillon (1894), Private Collection

3. Tell me about your thoughts that shaped one of my favorite sentences in the book, where Berthe is getting to know Manet. As she said: “I was baffled about my feelings for Manet. Was I falling in love with him, or did I wish I could be him?”

4. I myself have wondered for years whether Berthe and Edouard Manet were in fact lovers. When there is no concrete proof and letters have been destroyed, it’s hard to know for sure. What tipped the scale for you?

No, there is no concrete proof that Berthe and Edouard were lovers. And Berthe’s biographers have varying opinions. For me, Edouard’s portraits of Berthe tell the tale. For one thing, he painted more portraits of her than of any other model, and he never parted with any of them. One of Berthe’s biographers, Margaret Shennan, refers to the relationship between Berthe and Edouard as “a dialogue of two intelligences.” They were of the same social class, so it was possible for them to get to know each other in the first place. The two met their intellectual and artistic matches in one another. And just look at the paintings, which range from flirtatious to downright steamy. Can anyone look at Reclining and tell me that Berthe and Edouard were not lovers?

5. I never before understood what an enormous impact the Franco-Prussian War had on the Morisot family and particularly Berthe’s health. What sources did you rely on to dig into that period in the Passy neighborhood? Do you think her health issues from the war contributed to her early death?

Every book I read about Berthe or Edouard discussed the war. The Judgment of Paris: The Revolutionary Decade That Gave the World Impressionism, by Ross King, and The Greater Journey: Americans in Paris, by David McCullough are two non-academic books that offer harrowing descriptions of Paris during war and its aftermath.

Most definitely, the deprivations Berthe suffered during the siege of the Franco-Prussian War left her lungs permanently weakened. She suffered from bronchitis every winter for the rest of her life, and when she contracted pneumonia during the winter of 1894, that illness was too much for Berthe to withstand.

- I am surprised to learn how many men of this time period were afflicted with syphilis. In the novel, Berthe learns about Edouard Manet’s disease and says: “my sympathy for him transformed into utter rage that he would let his taste for women lead to the destruction of his genius.” How did you decide you had to address this issue?

It wasn’t a decision; I wasn’t going to dissemble about the cause of Edouard’s death. But I made the effort to put it in context to emphasize the dark side of the City of Light. Even Berthe, who lived a sheltered life, knew that one in five Parisian men suffered from syphilis. And I also make a point of Berthe’s awareness of prostitution and illegitimate children. She was conscious of the light and shadow in life and was contemptuous of the enormous hypocrisy displayed by Parisian society. Later, that same contempt spilled over into her opinion of the ossified art establishment. That rebellious attitude shaped what was a radical life: she loved whom she chose to love, and she painted in the style she wished to paint.

- Tell me what made you want to write a book about Berthe. What was it in her artistic struggle that captured your imagination the most?

What spoke to me personally about Berthe’s story was what I think of as the prison of her privilege. While no women were permitted to attend l’Ecole des Beaux Arts, the prestigious state school that trained, exhibited, and provided patrons for its students, there were some art schools open to working class women. Rosa Bonheur, the artist Berthe and Edma idolized, ran such a school herself. But it was deemed unseemly for upper-class girls to attend a school that prepared students to earn their livings as artists. Girls like Berthe did not pursue professions or enter the commercial world to any degree.

I’ve often wondered how life might have been different if Berthe had attended a women’s art school. She would have had many more artistic colleagues, to fall back on when Edma gave up painting. And with more artists with whom she could exchange ideas, Berthe might have developed her own style earlier in life, saving herself years of paralyzing self-doubt.

* * *

About the Author

Author Paula Butterfield taught courses about women artists for twenty years before turning to writing about them. La Luministe, her debut novel, earned the Best Historical Fiction Chanticleer Award. Paula lives with her husband and daughter in Portland and on the Oregon coast.

X

Author’s Statement:

Berthe Morisot was a fist in a velvet glove. In 19th century Paris, an haute-bourgeois woman was expected to be discreet to the point of near-invisibility. But Berthe, forbidden to enter L’École des Beaux Arts, started the Impressionist movement that broke open the walls of the art establishment. And, unable to marry the love of her life, Édouard Manet, she married his brother. While she epitomized femininity and decorum, Morisot was a quiet revolutionary.

Author Contact:

You must be logged in to post a comment.