Anna Ancher (1859-1935) is a hugely popular artist within Denmark, but she and her paintings are much lesser known beyond Scandinavia. Thankfully that is beginning to change.

The National Museum of Women in the Arts in Washington, D.C. hosted an exhibit in 2013 called A World Apart: Anna Ancher and the Skagen Art Colony, bringing a comprehensive collection of Anna Ancher’s work to the United States for the first time. I first encountered her art more recently, when I saw two of her paintings in a traveling exhibit sponsored by the American Federation of the Arts entitled Women Artists in Paris 1850-1900 (previously written about here). As wonderful as those two exhibits were, it is a rare event to witness Anna Ancher’s work outside of Denmark.

Anna Ancher deserves wider recognition because her work in oil and pastel is truly remarkable. Given the fact that she was born and raised in a small village at the northernmost tip of Denmark and received little formal training, her understanding of form, color, light and shadow is exceptional. She deserves to be ranked among the best 19th century artists, including Degas, Cassatt and Morisot.

In addition to her surprising talent, her story is inspiring and instructional for anyone interested in the gender struggle of women artists in the late 19th century. While American and French women artists fought to be taken seriously during this time period, Anna Ancher received great encouragement and recognition from her family, fellow artists and the official art world in Denmark. She didn’t have to forsake marriage and family for her career. According to our 21st century vocabulary, here was a woman who seems to have had it all. So what was her secret? What was the difference? My curiosity took me all the way to Copenhagen.

The Hirschsprung Collection in Copenhagen hosted a 2018-19 exhibition called Michael Ancher and the Women of Skagen. At the same time, the museum hosted an exhibit called the Allure of Color: Pastels from Anna Archer to P.S. Kroyer. What an opportunity to get acquainted with this exceptional woman.

Anna Ancher, (sounds like “anchor” in Danish) née Brøndum, was born in Skagen, a small little fishing village on the northernmost point of Denmark. Her parents ran an inn, where she was lucky to meet visiting artists who came to paint the raw coastal scenery in the summer. Inspired by these visiting artists, she began to draw at an early age.

The painter Michael Ancher arrived in Skagen the summer of 1874, when Anna was 16 years old and he was 10 years her senior. Michael had received academic art training at the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts in the 1870s, and was drawn to the seaside to capture large-scale scenes of fisherman and their nets. The village became widely known in artist circles when Michael exhibited in Copenhagen. The next summer Michael Ancher was joined by his artist friends Karl Madsen and Viggo Johansen. The artists stayed at the Brøndum family inn and they encouraged Anna to take professional training to develop her talents.

Anna’s mother, Ane Møller Brøndum, was a strong intellectual woman who ruled the family inn while pursuing an independent study of literature and history. Although she joined a very strict evangelical religion, she still allowed her daughters to pursue an education and associate with the visiting artists who were considered radicals.

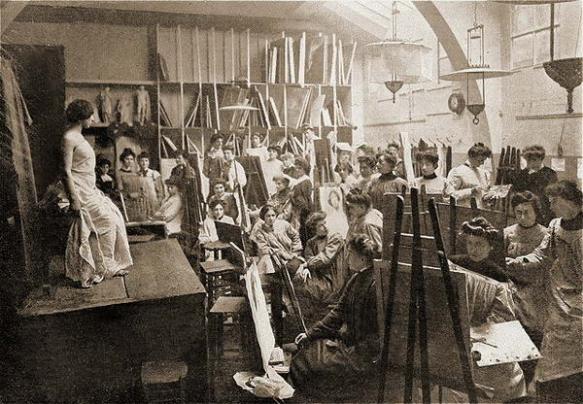

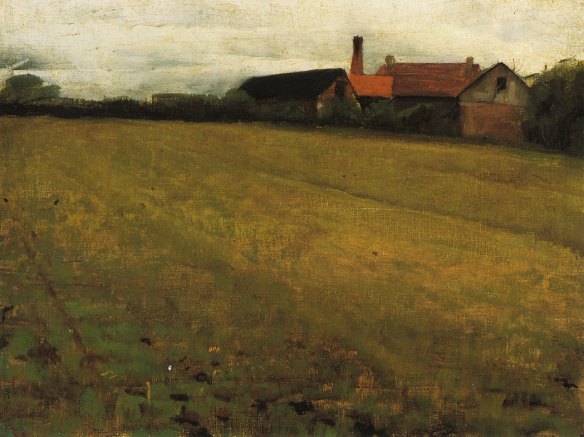

As progressive as Denmark is supposed to have been, women were still not allowed to attend the Royal Danish Academy of Art until 1888. So instead, Anna’s parents sent her to Vilhelm Kyhn’s private art school for women (Tegneskolen til Kvinder) in Copenhagen. Vilhelm Kyhn was a highly talented landscape painter in the naturalist tradition. He had been trained at the Royal Academy, but after a series of quarrelsome spats with the Danish art establishment, he broke off and started an alternative studio for other dissatisfied artists, including women. Thus, Anna received traditional instruction in painting and drawing, with an emphasis on the Golden Age of Danish painting (1800-1850). Luckily, her training was more rigorous than one would expect from a women’s art school at the time.

Anna spent three winters studying in Copenhagen, with summers in Skagen. The visiting artists continued to gather at her parents’ inn in the summer, where she must have benefited from their advice, demonstrations and no doubt some of their casual artistic banter.

Anna and Michael Ancher developed a romance and announced their engagement in 1877. Perhaps her parents insisted on a delayed wedding date, or perhaps the pair just didn’t feel as if they had enough financial security to tie the knot at the time. When Michael achieved a significant degree of artistic success in 1881, they married.

During their long engagement, Anna and Michael welcomed new international artists to Skagen, including Karl Madsen, who had studied in France and Germany. Anna was exposed to new ideas by leading European artists in a relaxed and nurturing setting. Perhaps it also helped Anna to have a fiancée and parents nearby to prevent unwanted attention or gendered ridicule from other male artists. She had allies.

Anna’s painting and pastel skills developed quickly, from both her formal education in Copenhagen and the informal lessons in a thriving art colony. In 1880, she made her début as a professional artist in the Charlottenborg Spring Exhibition in Copenhagen. She sold a pastel and received good reviews. The painting below, part of her début exhibit, shows her sophistication and talent at the young age of 20.

After Anna married Michael Ancher in 1881, her dedication to art intensified. Michael considered his wife an equal partner and supported her artistic ambitions. Together with her artist husband, Anna had more artistic opportunities than she might have had on her own. In 1882, the couple received government funding to travel to art centers in Berlin, Dresden, Vienna and Munich. Although she may have lived on an isolated tip of Denmark, Anna was able to travel to see major art exhibitions in leading art centers of the world.

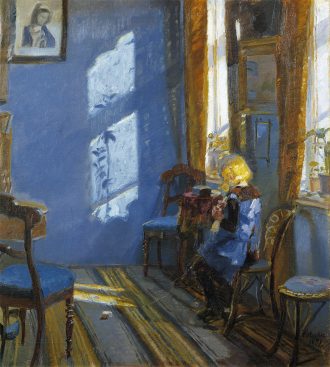

Anna had two major accomplishments in 1883: first, her painting The Maid in the Kitchen, shown below, an exquisite painting that displays a sophisticated use of color and light, and second, the birth of her daughter Helga, a golden-haired girl who would remain their only child.

Michael Ancher’s portrait of Anna while she was pregnant that reveals a deep respect and admiration for his wife. At the time, however, it was controversial. This was considered a pose appropriate only for royalty, and with the dog’s nose so close to her pregnant stomach, it would have been considered immodest. What woman wouldn’t want a husband who values her more than he values tradition and modesty?

Anna and Michael enjoyed collaborating on their art. So much so that in 1883, they created a joint painting, where each painted the portrait of the other. Quite an amazing project, as I wrote about here.

In 1884, Anna, Michael and Helga moved into a small house a few minutes away from her parents’ inn. The Anchers were able to pop down the street to join the Brøndums for dinner, sparing Anna from having to prepare family meals. Anna also enjoyed the double benefit of having her own maid: not only was she spared many domestic and child-rearing chores, she also had an artist’s model at her disposal all day long. That is why The Maid in the Kitchen (above) should be appreciated as a decidedly feminist statement. The artist is behind the easel, and not behind the sink.

Even after the birth of their child, Anna continued to travel to European art destinations from Amsterdam to Paris. Perhaps her parents helped out with child care, or perhaps they brought their young daughter along on their travels. In 1889 she and Michael visited Paris for six months, where they both exhibited and won prizes in the Paris World’s Fair. In addition, Anna took instruction from the famous French artist Puvis de Chavannes.

In 1891, Anna executed an ambitious work called A Funeral, an impressively large 48′ x 57″ piece, featuring multiple subjects in a serious setting, not unlike a previous work of her husband’s, The Christening. This painting reveals a mastery of color, while at the same time conveying a distinct impression of calm and control. Purchased by the Statens Musem for Kunst in 1891, this painting elevated Anna’s status as an artist even further.

Anna often painted their daughter Helga, as well as light-dappled interiors. She was known for her observation of light as it fell across a room, creating patterns of its own.

In 1893, Anna’s work was represented in the Chicago World’s Fair. In 1894 she was a member of a committee of Danish women who organized a Women’s Exhibition in Copenhagen. From 1900 on, Anna received many medals and honors, elevating her to a membership in the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts.

Interestingly, Michael and Anna’s daughter Helga grew up to be an artist as well. She was admitted to the Danish Royal Academy of Art School for Women in 1901, and studied art in Paris in 1909-1910. The pastel below reveals her mother’s strong influence.

Michael Ancher died in 1927, Anna in 1935. Their memory lives on at the Skagen Museum, first founded in the dining room of the Brøndum Inn in 1908. Today the museum includes the historic Ancher Hus, the home of Anna, Michael and Helga Ancher. After Helga’s death in 1964, their home was restored and turned into a museum.

Such a fascinating woman, especially for her time and place. The fact that she lived in such an isolated and beautiful spot might have actually been the secret to her success. In contrast to many other women artists of the 19th century, who struggled against a family and culture that valued modesty, propriety and conformity, Anna was lucky to grow up in an art colony that encouraged her talent and stoked her ambition. Artistic expression was her birthright.

What a difference.

You must be logged in to post a comment.