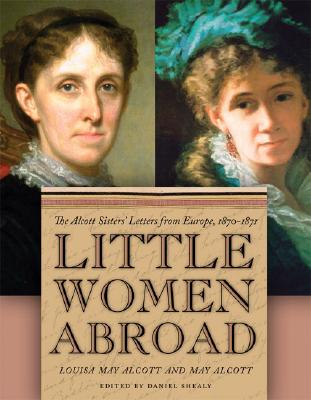

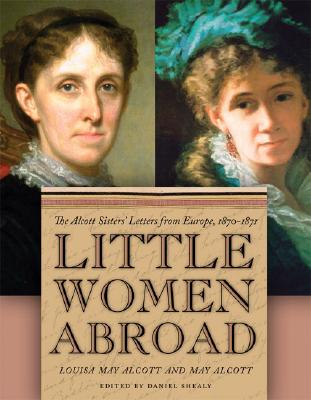

Little Women Abroad, edited by Daniel Shealy (University of Georgia Press, 2008), is a wonderful account of the Alcott sisters’ trip to Europe together in 1870. Most readers will be interested in the travels and insights of the most famous sister, Louisa May Alcott, but for an artist, the real thrill is to see France through her little sister Abigail May’s eyes.

Little Women Abroad, edited by Daniel Shealy (University of Georgia Press, 2008), is a wonderful account of the Alcott sisters’ trip to Europe together in 1870. Most readers will be interested in the travels and insights of the most famous sister, Louisa May Alcott, but for an artist, the real thrill is to see France through her little sister Abigail May’s eyes.

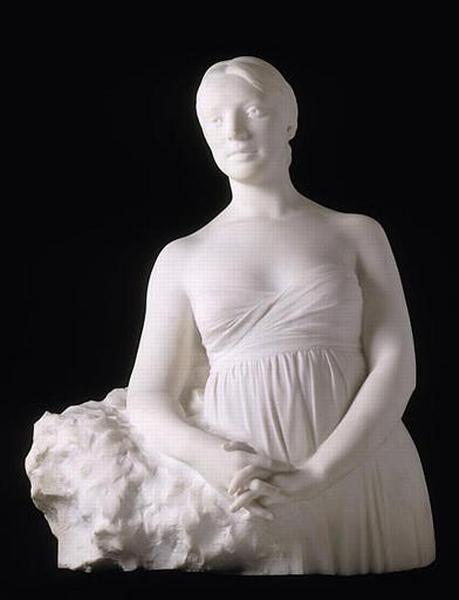

Most of us know Amy, the precocious little sister in Little Women who dreamed of becoming an artist. Few of us know much about Louisa’s real little sister Abigail May Alcott Nieriker (“May”), who did indeed grow up to be an accomplished artist. Unfortunately, May’s story ends tragically. She married at the age of 38, only to die one year later after giving birth to her first child.

May Alcott began to study art in 1856 when she was just sixteen years old. She studied with Stephen Salisbury Tuckerman, William Rimmer and finally William Morris Hunt, all of whom offered single-sex studio classes for Boston women. Hunt had studied at the Ecole des Beaux Arts in Paris and no doubt extolled the virtues of study abroad. May’s fellow students such as Elizabeth Boott, Sarah Wyman Whitman and Elizabeth Bartol were all making plans to study in France by the late 1860s and early 1870s.

After Louisa May Alcott achieved financial success with Little Women in 1868, the two sisters planned a trip to Europe with their friend Alice Bartlett. The women traveled by the French steamship Lafayette and arrived at the western port of Brest in Brittany in April, 1870.

It was May’s first trip to Europe and she was completely enchanted with France. Their first extended stay was in Dinan, a lovely medieval town in the middle of Brittany. May sent home sketches of a variety of scenes throughout Dinan, many of which are nicely reproduced in Little Women Abroad. It appears that all of May’s sketches were in pencil or pen and ink. In one of her letters, she said she wished she had been trained how to paint en plein air so she could capture the beautiful colors. Nevertheless, her sketches are sufficient to be able to identify the buildings and ruins which still stand today.

Here is a Google Map of the Alcott Sisters Sites in Dinan, in case you’re lucky enough to venture there yourself someday. Dinan is a beautiful little city which makes for a lovely day trip from a larger home base in Brittany such as St. Malo. Dinan has 13th century castles, gothic churches, bell towers, narrow winding streets and beautiful timbered architecture.

Until you can get there yourself, here is a photo tour of the Dinan sites in Little Women Abroad, starting with the building that once housed the pension in which the Alcotts stayed. It was just outside the fortified walls of the town, next to the Porte Saint Louis and just down the street from the Dinan Castle.

14 Place Saint Louis, Dinan, France, the location of Madame Coste’s pension where the Alcott sisters stayed from April to June, 1870. As Louisa May Alcott described it in a letter dated April 24, 1870: “We are living, en pension, with a nice old lady just on the walls of the town with Anne of Brittany’s round tower on the one hand, the Porte of St. Louis on the other, and a lovely promenade made in the old moat just before the door.”

The plaque in the wall at Place Saint Louis, Dinan, France

The Porte Saint-Louis, located next to the Pension de Madame Costes

The Dinan Castle (which Louisa May called Anne of Brittany’s Round Tower), located just down the road from Place Saint Louis. Built in the 1300s.

The view of Dinan from atop the Dinan Castle. As May said in an April, 1870 letter to her mother: “From the top of her [Queen Anne’s] tower is the most superb view all over the country, and I am expecting great things in going to see it.”

May Alcott spent her time sketching throughout the medieval village, so full of “enchanting old ruins, picturesque towers and churches, and crumbling fortifications, that it almost seems like a dream.” There were so many good scenes for sketching that she didn’t think she could do them justice. As May said in a letter home:

I long to make pictures on every hand, but get extremely discouraged when I try, as it needs all the surroundings to make the scene complete.

May recommended Dinan to her fellow artists in a guidebook she would later write:

Here an artist can rest with delight for many months, as everything from the adjacent country, which is thought to be the most beautiful in Brittany, to the ancient gateways and clocktower in a street so narrow that the gabled roofs meet overhead, is sufficiently attractive to keep the brush constantly busy.

May visited or sketched nearly everything in town, from the Basilica of St. Saveur:

“Yesterday we went to some lovely gardens surrounding the most beautiful gothic church.” – May Alcott, letter dated April 20, 1870 . This is a photograph of the small park and gardens that stand behind the Basilica St-Saveur today. Originally built in the 11th and 12th centuries, a Gothic chapel was added in the 15th century.

to the Viaduct of Dinan over the River Rance:

!["The grand viaduct which, according to Murray [the Alcott's 1870 guidebook to France] is about the finest in the world, fairly took away my breath." -- May Alcott in a letter to Anna Alcott dated May 30, 1870](https://americangirlsartclubinparis.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/04/img_3330.jpg?w=584&h=438)

In a letter to Anna Alcott dated May 30, 1870, May Alcott said: “The grand viaduct which, according to Murray [an 1870 guidebook] is about the finest in the world, fairly took away my breath.”

The grand viaduct across the River Rance in Dinan is still breathtaking. The day I was there the local rowing club was preparing for practice on the other side of the river.

May sketched the Porte of Jerzual and the steep little rue de Jerzual, which winds down from the upper village to the river, and is lined with timbered old shops that lean in over the cobblestoned street:

Porte du Jerzual, Dinan, France

A scene from rue de Jerzual in Dinan. As May said in a letter home dated April 29, 1870: “Yesterday we went down the oldest street in town, (where, in spite of the steepness, Queen Ann’s carriage is said to have trundled over it), to the river which runs at the foot. The houses overhang the street in funny little gabled stories almost shutting out all light from above, and it being very narrow & extremely steep, you can see it was a sensation to have explored it.”

In their letters home, the Alcott sisters both mention their visit to the neighboring village of Léhon, which is just a mile or so down in the valley from Dinan along Route D12. Louisa May wrote home after going to a fair in the village and said (in a letter dated April 20, 1870):

May is going to sketch the castle so I won’t waste paper describing the pretty place with the ruined church full of rooks, the old mill with the water wheel housed in vines, or the winding river, and meadows full of blue hyacinths and rosy daisies.

The remains of the Léhon castle in the background.

The Abbey Church in Lehon, France, once sketched by May Alcott

The River Rance through Léhon, France.

The Alcotts also visited the Chateau de la Garaye, a lovely site located just a couple of miles from the village of Dinan. May wrote home to tell her mother about the beautiful ruins there:

I have tried to sketch from memory a lovely old ruin, where we spent the day yesterday, but can give you a very indefinite notion of the gray old tower with ivy clinging to it in all directions, the rear walls having all crumbled away. The blue sky shone through the little ornamental windows in a way that was quite enchanting. It is only about two miles from Dinan and a pretty walk though the wood to the moat and great embattled walls, which surround the chateau.

Alice and I walked, while Lu went down in a donkey carriage. . . . We found a large party of English people already at the castle sketching it with pencil in colors. . . .

The ruins of the Chateau de la Garaye still stand today. “The blue sky shone though the little ornamental windows in a way that was quite enchanting.” — May Alcott, April 1870. It makes me so glad to know some things just don’t change in over 140 years.

My own colored pencil sketch of the ruins of Chateau de la Garaye

May Alcott’s Life Beyond Dinan:

After the Alcott sisters left Dinan in the summer of 1870, they continued their European travels and proceeded to the Loire Valley, Switzerland and Italy. They found themselves the middle of the Franco-Prussian war which broke out that July but managed to find safety in Switzerland, along with many other refugees from Paris and Strasbourg. Louisa May returned to Boston the next summer, but May went on to study art in London on her own and didn’t return until November, 1871, when she was called home to help the rest of the family.

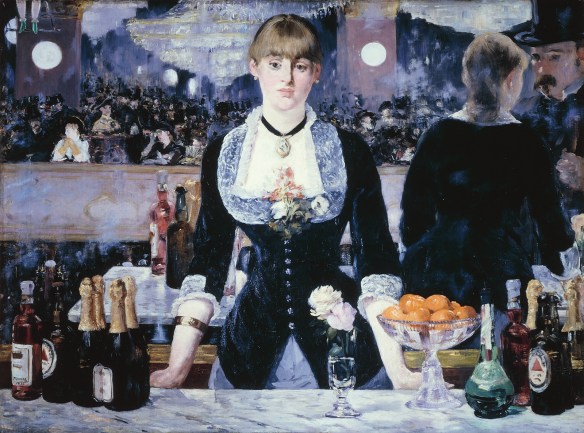

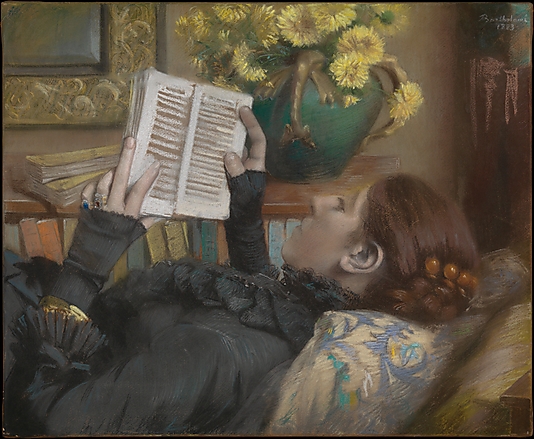

May Alcott returned to London and Paris in 1873 and then again in 1876. She would study at the Academie Julian in the Passage des Panoramas in 1876-77, and would attend the Paris Salon of 1877 where her own still life painting would be exhibited. She would be invited to Mary Cassatt’s home for tea, and would travel to the rather bohemian art colony in Grez in the summer of 1877. She was living a ground-breaking life as an American expatriate female artist.

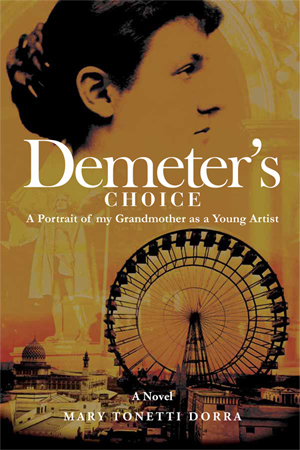

In late 1877, while May was living on her own in London, she would learn that her mother had died. In her grief she developed a quick romance with Ernest Nieriker, a young Swiss businessman fifteen years her junior, to whom she would become engaged in March of 1878. The newlyweds would move to a lovely little home in the suburbs of Paris, where she dreamed of combining a career in art with marriage and a possible family. She would have yet another painting accepted in the Paris Salon, and would publish a guidebook for women artists called Studying Art Abroad and How to Do it Cheaply. At the end of 1878, May’s personal life and her art career were making gratifying moves forward.

But then, in December of 1879, May Alcott Nieriker died six weeks after giving birth to her daughter Lulu. She was only 39 years old. Baby Lulu was first sent to live with her aunt Louisa May in the United States, but when Louisa May died just nine years later, young Lulu was returned to her father in Switzerland.

We are lucky to have been left with such a prolific record of May Alcott’s remarkable travels and experiences, even if they were short-lived. Thanks to the details and sketches provided in Little Women Abroad, we can follow along. It’s worth the trip.

!["The grand viaduct which, according to Murray [the Alcott's 1870 guidebook to France] is about the finest in the world, fairly took away my breath." -- May Alcott in a letter to Anna Alcott dated May 30, 1870](https://americangirlsartclubinparis.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/04/img_3330.jpg?w=584&h=438)

You must be logged in to post a comment.