I found another lovely art history novel that I think you really must read. If you loved Girl With a Pearl Earring by Tracy Chevalier, chances are you’re going to enjoy this one too.

The Anatomy Lesson by Nina Siegal (Doubleday, 2014) tells the story behind The Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Nicolaes Tulp (1632), Rembrandt’s famous painting from the Mauritshuis in The Hague.

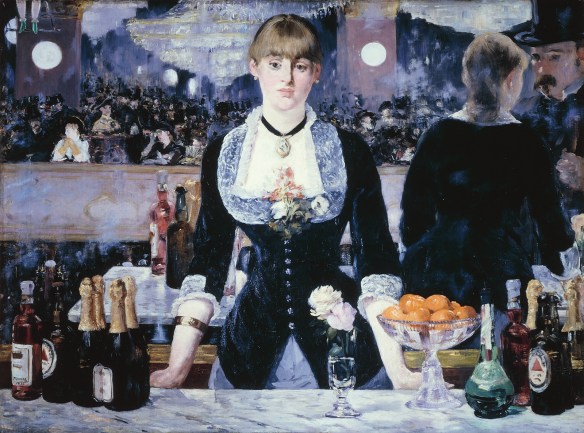

I love novels based on famous paintings (the list goes on and on: The Goldfinch, The Painted Girls, The Girl in Hyacinth Blue, The Luncheon of the Boating Party, so many that I think I need to do a follow-up post). But still, I couldn’t help but wonder, why would Nina Siegal choose this painting to write about? After all, it’s a bunch of Dutch guys goggling over a cadaver, right?

The story behind a public autopsy in Amsterdam in the 1600s seems like a difficult subject for a novel, certainly less approachable than writing about Vermeer’s pretty girl with a pearl earring. But Siegal was meant to write this story. She grew up with a reproduction of this painting in her father’s study and has been intrigued with it all of her life.

Siegal was drawn into reading nonfiction accounts of Rembrandt’s life as well as the people and the cadaver pictured in The Anatomy Lesson. There were conflicting stories about the people behind the painting, which left Siegal a great deal of creative freedom to plan her own narrative. I think she did a marvelous job.

The story is told from alternating points of view including Rembrandt, Dr. Nicholaes Tulp, the French philosopher René Descartes, the dead man, a coat thief named Aris Kindt, as well as Aris’s sweetheart Flora. Each character adds interest and depth to the portrait, but it is the sympathetic love story between Aris and Flora that brings it to life.

When Rembrandt meets Flora and learns more about Aris’s story, Rembrandt is inspired to go far beyond the intent of the original commission – which was to make a portrait of the town’s elite Amsterdam Surgeon’s Guild – and to create a masterpiece that would honor Aris’s short tragic life.

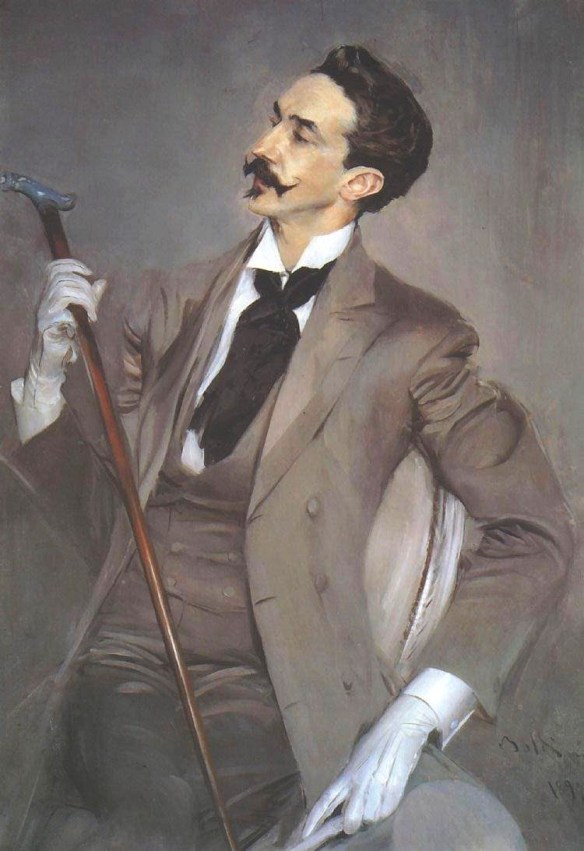

Rembrandt, Self-Portrait, c. 1632, Kelvingrove Art Gallery and Museum, Glasgow, Scotland. Rembrandt made dozens of self-portraits throughout his career, but this one was made the same year he painted The Anatomy Lesson. It is the first portrait where he is starting to look like a successful painter. The success with The Anatomy Lesson did indeed launch his career.

I guess it’s no surprise that the scenes where Rembrandt was actually planning and executing the painting were my favorites. Siegal did a beautiful job of explaining how Rembrandt used highlights to create the mood and focal point of the scene, and why he didn’t display the body cut wide open during the autopsy.

I brought my lantern closer to the easel again. What if I were to illuminate Adriaen, to bring him into the light? If he were not sliced open and degraded but instead elevated and lit? What if I did not show the power of the men over him but his own power over them?

. . .

As I continued to dab my paintbrush into the Kassel earth and bone black, I recognized what was possible through this portrait. I could make a broken man whole. I added some lead white to my palette and painted on, . . . adding color to the flesh so that it was pristine.

Reading this book you get a sense that young Rembrandt is at a turning point in his life, and that he is about to become the master painter that we all know today. When Siegal has him pick up his paintbrush to finish The Anatomy Lesson, you feel as if this is the moment that his genius was sparked.

Most art travelers know that Amsterdam is the home of the Rijksmuseum and the Van Gogh Museum. But if you’ve never been to the Rembrandt House Museum in Amsterdam you really need to put it on your Art Travel Bucket List. It’s a complete gem.

Rembrandt bought the house in 1639, just a few years after he painted The Anatomy Lesson, the same year he was commissioned to paint Nightwatch. He was living large, but only for the next 15 years. He went bankrupt in 1656 and was forced to auction off his house and assets. Luckily, the house was never torn down and was bought by the city of Amsterdam in 1906. It has been beautifully restored to the condition it would have been in during Rembrandt’s day, including many reproductions of his own and other paintings he collected. The museum staff offers daily art demonstrations in the etching and painting studios.

If you can’t get there soon, maybe you can still enjoy my photos. They’re not the best quality, but you get the idea.

The Anatomy Lesson by Nina Siegal: Highly recommended

The Rembrandthuis in Amsterdam: Also highly recommended

For further reading: I highly recommend another historical novel set in Amsterdam: History of a Pleasure Seeker by Richard Mason. Read my post about that book and the Willet-Holthuysen Museum in Amsterdam here.

e & Treasure

e & Treasure

You must be logged in to post a comment.