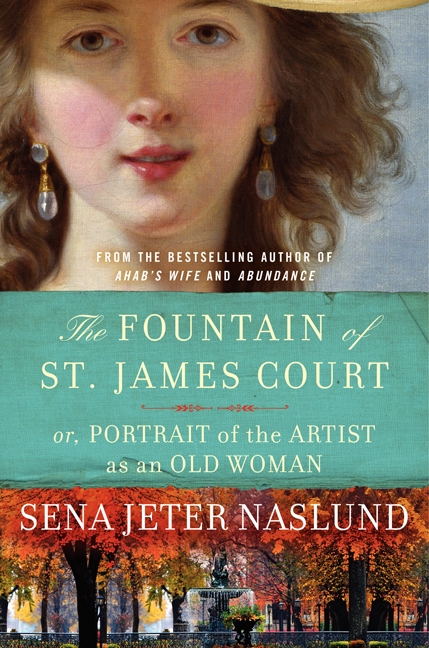

Sena Jeter Naslund (the author of nine other novels, including my own personal favorites Ahab’s Wife and Abundance, A Novel of Marie Antoinette) has written a marvelous new novel focusing on the life of Louise-Elisabeth Vigée Le Brun, a highly successful female portrait artist in 18th century France.

Vigée LeBrun’s own self-portrait (Self Portrait in a Straw Hat) gazes out at us from the book cover with an expression of confidence and contentment. Here is a woman who knew who she was and how to paint it.

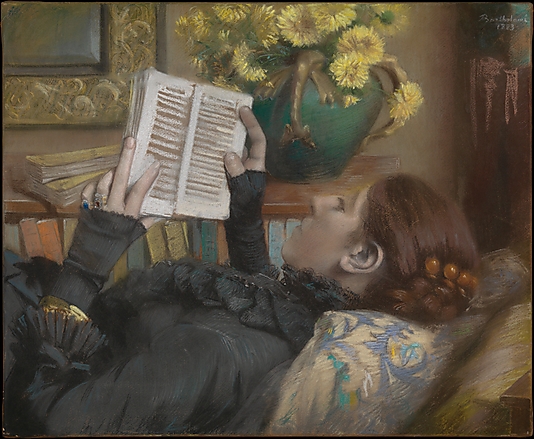

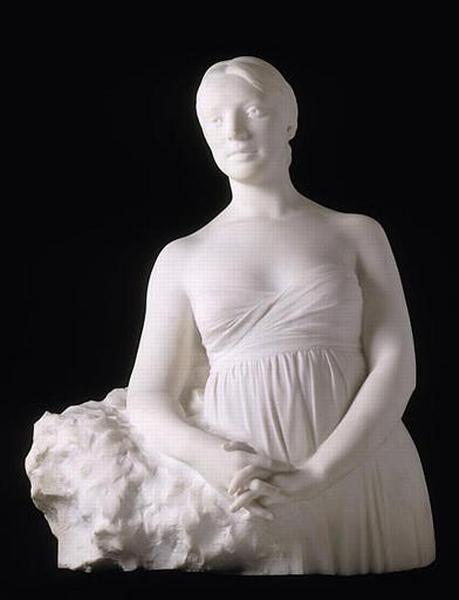

Check out the full portrait below. Look how confidently Vigée Le Brun paints the light falling across her face, the glisten of her own lips, the cool shadows of her neck. And her hands, one firmly holding the tools of her profession, and the other, open, extended, and more feminine, welcoming the viewer’s closer scrutiny. The earrings, the flowers, the bows and the beauty: here I am, it says, I am a woman painter.

Self-Portrait in a Straw Hat by Elisabeth Vigée Le Brun (1782). Original in a private collection, copy at the National Gallery of London. (Source: Wikipedia)

The Fountain of St. James Court is much more than a biography of Vigée LeBrun’s life; its subtitle also makes clear that the book is an exploration of the lives of mature women artists, with a nod to James Joyce’s Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man. To me, the subtitle is a challenge: yes, Joyce’s portrait of a young man is masterful, but an equal if not superior wonder, is how female artists sustain joyful work over the course of a long and challenging life.

To answer this question, the novel follows a day in the life of Kathryn (“Ryn”) Callahan, a 69 year-old author who lives by herself in an older neighborhood known as St. James Court in Louisville, Kentucky. She has just finished the manuscript for her ninth novel, the story of Vigée Le Brun. Ryn spends much of the day contemplating her long artistic life that has included three unsuccessful marriages but many well-cultivated friendships, a satisfying career, and a devoted relationship with one adult son.

The two threads of this novel work together to explore the lives of women artists, who have so very much in common even though they are separated by over 200 years.

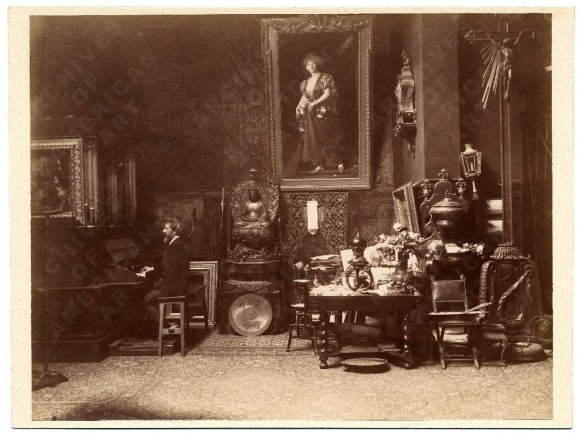

It’s probably no surprise that my favorite story line was that of Vigée LeBrun, who was born in Paris in 1755. Her father was an artist who gave Elisabeth her first set of pastels and allowed her to sit in on the evenings he hosted with the (male) artistic circles of Paris. By the time Elisabeth was 13 years old it was clear she was a gifted artist: she began taking art classes at the Louvre and painting stunning pictures of friends and family.

Portrait of The Artist’s Mother, Madame Le Sevre (painted around 1768-70, when Elisabeth would have been only 13-15 years old.) This painting was sold for $122,500 at a Christie’s auction in 2012. (Source: Christies.com)

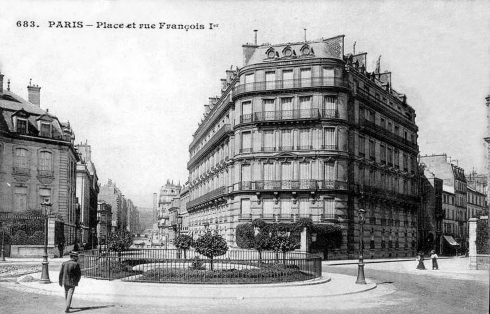

After the death of Elisabeth’s father, her mother insisted on moving to a more fashionable neighborhood on rue St. Honoré overlooking the terrace of the Palais-Royale, where they could meet more of the aristocracy who would support Elisabeth’s painting career. Soon Elisabeth is painting the portraits of Dukes and Duchesses, including the Duchesse de Chartres and the Comtess de Brionne.

The gardens of the Palais-Royal, where Vigée Le Brun once strolled alongside the French aristocracy. Today it’s still a lovely place for a walk or a picnic, with or without the aristocracy.

The carefully manicured trees cast dapples of shade in the gardens of the Palais-Royal, just as they would have 250 years ago in the days of Elisabeth Vigée Le Brun.

At the age of 20, Elisabeth married M. Le Brun, Parisian art dealer with whom she shared a love of art. Like her stepfather, her husband claimed all of her commissions, which was his legal right, and spent much of it on gambling and extravagant women. Elisabeth painted on, learning that “[a]s long as I can paint, I will always be happy.”

By the time she was 23, Elisabeth had been invited to Versailles to meet Marie Antoinette. Elisabeth was known for her flattering pictures of society women, so it was hoped that her paintings would present a more positive image of the increasingly unpopular queen. Elisabeth became a part of the royal inner circle and the royal family’s portraitist, making over 30 paintings of the queen and her family between 1778 and 1789.

Marie Antoinette by Elisabeth Vigée Le Brun (1778). Supposedly, Le Brun made 6 copies of this painting. Two are in the French state collection, one was lost or stolen when the US congress was burned by the British in 1812, one was given to Catherine the Great (location now unknown) and two others are missing.

Marie Antoinette and Her Children by Elisabeth Vigée Le Brun (1787). One of the last paintings Elisabeth would ever make of the royal family before the revolution tore them away from Versailles. The painting can still be seen in the Palace of Versailles.

Vigée Le Brun’s career was not without controversy or criticism. She had to withstand the usual rumors about women artists: that she did not do her own work, that a man had to do it. Sena Jeter Nasland serves up a great line for Elisabeth’s response to this criticism in the book:

When I first hear the exclamation “Why, she paints like a man!” I am pleased; I take it only to mean that my work is truly excellent. But insult is also intended, and the innuendo, indeed the idea is expressed overtly, that my brush is my manly part!

Naslund’s story, then, serves as an obvious reminder that artistic gifts are not delivered on the basis of sex. But it is also so much more. It reveals the inner lives of gifted women who are learning not to discount themselves because of their sex or their age.

No matter how they compare to James Joyce’s Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, Naslund’s portraits of Elisabeth Vigée Le Brun and Kathryn Callahan will likely stay with you for a long time. If you’re like me, you’ll find yourself dog-earring your book so you’ll be able to share all of your favorite passages with your book club.

The Fountain of St. James Court, or, Portrait of the Artist as an Old Woman by Sena Jeter Naslund (Harper Collins 2013): Highly recommended.

Also recommended for further reading:

The Project Gutenberg ebook of Vigée Le Brun by Haldane MacFall: http://www.gutenberg.org/files/30314/30314-h/30314-h.htm

The Project Gutenberg ebook of The Memoirs of Madame Le Brun by Marie Louise Elisabeth Vigée Le Brun: http://www.gutenberg.org/files/31934/31934-h/31934-h.htm

Related articles

- TLC Book Tour: The Fountain of St. James Court or, Portrait of the Artist as an Old Woman (beccasbyline.wordpress.com)

!["The grand viaduct which, according to Murray [the Alcott's 1870 guidebook to France] is about the finest in the world, fairly took away my breath." -- May Alcott in a letter to Anna Alcott dated May 30, 1870](https://americangirlsartclubinparis.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/04/img_3330.jpg?w=584&h=438)

You must be logged in to post a comment.